THE LEADER’S PART-TIME ABSENCE: DIFFICULTIES AND ATTEMPTED RESOLUTIONS IN A RESIDENTIAL CHILD CARE SETTING – BY PATRICK TOMLINSON (1995)

Date added: 09/05/20

Download a Free PDF of this Article

LEADERSHIP DYNAMICS

Editorial by David Kennard

With the increasing emphasis on training and qualifications, many of us go on courses that take us away from our work roles and relationships for part of each week. How do we feel about this and handle it? How do those we leave behind each week feel about it and react? What happens to the arrangements we try to put in place to cover for our absences?

With the increasing emphasis on training and qualifications, many of us go on courses that take us away from our work roles and relationships for part of each week. How do we feel about this and handle it? How do those we leave behind each week feel about it and react? What happens to the arrangements we try to put in place to cover for our absences?

Tomlinson addresses these issues from his own experience and helps us to think more clearly about these questions and their ramifications.

Reflection – Patrick Tomlinson (2024)

I wrote this article when I was working at the Cotswold Community, a therapeutic residential community for boys in Wiltshire, England. My role was Assistant Principal responsible for Staff Training and Development and this was the first article I had published.

Nearly 30 years on, I am reminded of it due to the same type of dynamics I find in consultancy work with organizations going through similar challenges. There are a few key points that are likely to be universal over time and place.

1. In therapeutic trauma services for children when a leader is absent it is likely to arouse primitive feelings such as abandonment and loss, and the feelings that go along with this such as anger, uncertainty, and insecurity.

2. In services for children who have suffered many adversities there is a high level of sensitivity towards the absence of parental figures. Absence easily arouses feelings of abandonment.

3. Feelings of envy towards the absent person are also likely. For example, the remaining staff may feel the absent person is privileged while those are left to deal with the hard work. And this may be more difficult than usual due to the absence. When a leader is absent in a service that requires a high level of emotional containment difficult behaviour can be a symptom.

4. When a leader is absent frequently over a long period confusion and uncertainty as to who is in charge is likely to arise. Does there need to be changes in authority and roles to accommodate the new situation?

5. Carrying on as if everything is normal can be a defence acknowledging the significance of the change. Paying attention to the reality of the changes involved may be avoided.

6. Issues of uncertainty and insecurity are likely to arise in the staff and children. This could lead to a feeling of unsafety which is likely to be acted out. Unless the reality of the absence and its implications are worked upon the acting out will most likely continue and escalate.

7. Containment processes such as supervision, team meetings, reflective spaces, and consultancy are essential to working with these dynamics effectively.

At the Cotswold Community we had many regular spaces for processing and thinking about what was going on. We had processes mainly for thinking about the therapeutic work with young people and others for considering matters of leadership, management, group and organizational dynamics. We had several external consultants to help us with this, such as the Child Psychotherapist, Barbara Dockar-Drysdale, and the Organizational consultant, Eric Miller. The design of the model was instigated by the Home Office in 1967 as an experimental alternative to the failing Approved School system.

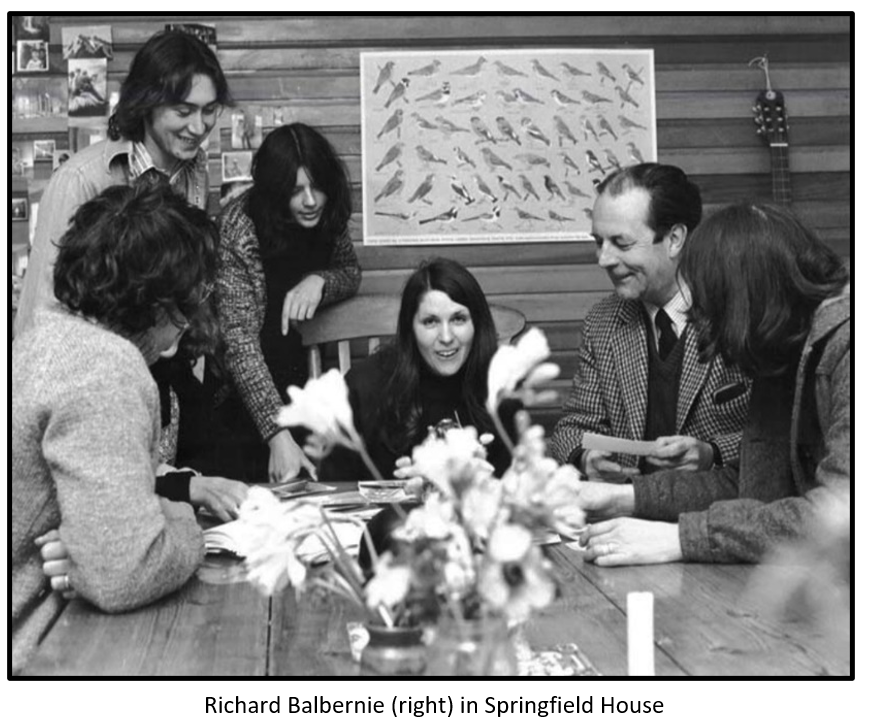

The change from an Approved School to a Therapeutic Community was a huge and difficult task which has been well documented by David Wills (1971) in his book, Spare the Child: The Story of an Experimental Approved School. Over time the impact was profound. Writing about Richard Balbernie who had been the Principal of the Community from the beginning, Eric Miller (1986) stated,

The change from an Approved School to a Therapeutic Community was a huge and difficult task which has been well documented by David Wills (1971) in his book, Spare the Child: The Story of an Experimental Approved School. Over time the impact was profound. Writing about Richard Balbernie who had been the Principal of the Community from the beginning, Eric Miller (1986) stated,

"Although Richard Balbernie was characteristically modest about his achievements, a follow-up study four years ago showed recidivism reduced from 85% to around 5%. But for the Cotswold Community literally hundreds of young men would be in and out of prison."

While Miller alludes to the possibility of prison, many of the young people may have had different outcomes without the intervention of the Cotswold Community. Some would have struggled with serious mental illnesses, and other difficulties in life, such as serious relationship and employment difficulties. And some of the young people may well have navigated themselves into a positive life. We know about the cycles of deprivation that can carry on from one generation to the next. The Cotswold Community aimed to break the cycle and for many young people it did.

As this article explains, we had ten boys living in four homes on one site, which was a 360-acre farm. We had small staff teams of care workers and other support workers. With ten boys in each home, we had to be highly effective to work well with the young people. Having a group living together provided great opportunities for group work, multi-faceted relationships, and the benefits of a peer culture.

We did not manage this effectively all of the time and group distubances could become difficult and unsafe. Without the high level of focus on staff support and development, and consultancy processes the task would have been impossible. The article gives an insight into the way we worked on complex and challenging situations. It shows how changes and insecurities in the holding environment, which in this case, included the staff team and the wider organization, are likely to be felt and ‘acted out’ in the behaviour of the young people. In the situation discussed here, the solution lies in fixing the environment. Once that was achieved the young people’s behaviour settled. The article also touches upon some interesting connected issues such as co-leadership dynamics, managing change, and envy.

THE LEADER’S PART-TIME ABSENCE: DIFFICULTIES AND ATTEMPTED RESOLUTIONS IN A RESIDENTIAL CHILD CARE SETTING – BY PATRICK TOMLINSON (1995)

Abstract: The temporary or part-time absence of a team leader or other staff for training purposes in a residential therapeutic community is an important and complex issue. This article explores the author's experience as a leader, absent part-time for training purposes, in a residential therapeutic child care setting. The context of the experience is described in terms of the workplace, the leader’s role within it, and the training course. The difficulties involved and how they have been worked with are examined concerning the following themes:

• managing staff absence specifically for long-term training;

• managing the part-time absence of the leader; managing change within a therapeutic community;

• and the nature of co-leadership compared with singular leadership.

Recommendations are made as to how the difficulties involved may be anticipated and worked on. Although specific to this case, parallels may be drawn to the management of staff absence for different reasons and in different settings.

Introduction

For two years beginning in October 1992, I started training as a student on the Postgraduate Diploma/MA course in Therapeutic Child Care at Reading University, whilst also working as a team leader at the Cotswold Community, a therapeutic community for emotionally disturbed boys (Whitwell, 1989, 1994).

In this article, I will examine how my absence has been managed, focusing on the difficulties that have been raised and how they have been resolved. I shall critically evaluate what seem to be the significant issues and themes developing throughout this process, especially concerning absence, the management of change and transition, and aspects of co-leadership.

To understand the implications of my absence, it seems important first of all to understand the context within which this has taken place, in terms of the work setting, my role within the setting, and the course.

The setting

The Cotswold Community is a therapeutic community for the treatment of unintegrated (Winnicott, 1988) boys, founded in 1967. The treatment approach is largely based on Dockar-Drysdale’s (1990) application of Winnicott’s theory. The management and organization of the Community are based upon a systems approach developed - in conjunction with consultants from the Tavistock Institute of Human Relations. The Community is managed externally by Wiltshire County Council and internally by the senior management team. The Community employs several consultants with specialist expertise.

Within the Community the boys live in four separate households, each of ten boys. Three of these are ‘primary’ households, to which new referrals are, admitted. These boys will have been assessed as unintegrated. The other household is the ‘secondary’ household and admits referrals from the primary households, once they have reached integration. All of these households have their work directly delegated and supervised by the Principal of the Community.

My Role

I am the team leader of Springfield, one of the three ‘primary’ households of ten boys aged between nine and fifteen years. I have been a team leader for six years and of Springfield for three years. Besides myself, Springfield has a staff of five care workers, two domestic staff, two education staff, and two volunteers. The staff work around seventy hours per week. All care and education staff live residentially. I manage the household boundary, providing the conditions in which treatment may be effective,

... it is clear that effective leadership requires the boundary position. (Miller 1989, p.8)

From this position, I provide containment (Bion, 1962) for the household. Bion likened the function of ‘containing’ to the function of the mother whose ability to receive and understand the emotional states of her baby makes them more bearable.

I also have considerable practical responsibilities alongside other team members in the day-to-day experience of group living. When I joined Springfield the group of boys and staff team were in a state of uncontained chaos. There was a high level of dependence on myself to help create some order and get things back on ‘task’ (Menzies Lyth, 1979). This was achieved within a year and the ‘household’ had just reached a point of feeling quite stable before I started the course.

The Course

The course at Reading University is a three-year course, with the first two years based on a once-weekly attendance at Reading for three ten-week terms and the completion of coursework for assessment. The third year is based on completing a research dissertation. The course is a combination of academic and experiential learning. As well as attendance at Reading it is also necessary to have one day per week for study purposes. The practical implications of this meant reducing my time working in Springfield from seventy hours per week to forty hours.

I was chosen by the Principal of the Community to join the course, based on my experience in the Community and the need for further training if I was to take on greater responsibility within or outside of the Community. I willingly accepted the opportunity. The community decided to employ another worker to help cover my absence in Springfield. I would maintain my position as the team leader with the deputy extending his role to cover my absence.

Beginning the Course

The idea of myself joining the course and the absence it would involve was discussed with my staff team and Community for several months before the course began, allowing everyone to express feelings connected to the change.

We gave careful consideration to the impact my absence may have and how best to use my time in Springfield. It was felt by myself, the staff team, and the Community, that I should spread my working time over as many days as possible, to maintain my contact with and management of, Springfield. The deputy’s role would be to ‘manage the gaps’. I would continue to represent the household within the Community and externally with social workers, parents, etc. On the other hand, I would cease supervising individual team members; this would be taken on by the deputy whom I would supervise.

We began this new pattern of working four weeks before the course started in October 1992, to give a transitional period, where I would still be on hand to some extent in case of major difficulties. As soon as we began, Springfield became uncontained. Boys began acting out much more than usual with a lot of ‘running off. It was quite rare that boys ‘ran off—now they were leaving the house in groups of three or four, running around the Community and outside of it, night and day, two or three times a week. This sense of uncontainment was also evident within the household, with events that were normally fairly settled, such as mealtimes, group meetings, and bedtimes, often being disrupted and breaking down into chaos. The general level of anxiety experienced by the boys and the staff team had increased significantly, with staff expressing an increasing concern that things were getting ‘out of control’.

At the time we were surprised by the extent of the difficulties. The following factors may have contributed to the situation:

a) Joining the course was a major change in itself. I had been working in the Community for eight years without any significant ‘absence’. This was a big change both for me and for all those involved. My anxieties about this change may have affected my capacity as a ‘container’,

b) The experience of having a worker on a course such as this, with the particular model that we had developed was new to the Community. This, alongside the anxiety created by having a worker going ‘outside’ of the Community to learn, may have also affected the containment of anxiety. The experience of ‘going outside’ may also have caused some excitement, and identification with this may have been a factor in the boys running off, to find their own experience of going outside’.

c) As well as the actual reasons for the absence, fantasies will also exist. Staff and boys may have experienced feelings of rejection and fantasized that I had found something more interesting or important, or could not bear them anymore and needed to escape. There may have been fantasies that I was doing something altogether different. For example, it was suggested by one of the boys that I was going to ‘raves’. It may help the level of containment and reduce acting out if these fantasies can be expressed and explored. This may be especially important in a client group for whom external reality is not easily separated from their internal reality. The changes for Springfield were considerable. New relationships would need to be established within the staff team, between boys and adults, between the household and Community, and between the household and the external world.

d) The ‘favoured’ absence of myself aroused considerable feelings of envy. In the very demanding work of the Community, opportunities such as I had are rare. Remarks made to me at different times by staff and boys alluding to the ‘cushy’ time I was having, suggested that envy and resentment were felt. It is possible that by ceasing my supervision meetings, the opportunity for staff to formally express and work through these feelings was blocked to some extent.

e) The absence of a ‘father figure’ in terms of my leadership role, caused particular difficulties in my setting. Unintegrated children have not managed to internalise containing relationships with ‘parental figures’. One of the central needs in our treatment setting is to establish trusting relationships between boys and staff. For this to happen there needs to be a high degree of continuity and reliability. Because of this incapacity to hold onto the image of a ‘parental figure’, during his/her absence, the need is very much for the actual presence of the ‘parental figure’. Also, the level of preoccupation involved in this work leads the workers ‘maternally’ involved with a boy to need the presence of a ‘father figure’ to support their work. I represented a ‘father figure’ in two different ways. As an absent man, feelings were evoked connected to memories of absent fathers, and in my role I acted as a ‘father’ in the sense that Winnicott (1956) described, protecting the mother-baby unity from impingement. The absence of the ‘father’ in these circumstances could lead to an increase in levels of anxiety for staff and boys.

f) Springfield’s previous history of uncontainment raised additional anxieties during my absence. The staff and boys were largely dependent on me for ‘containment’.

g) I anticipated some of the difficulties involved in joining the course, but I did not anticipate the difficulty in managing the relationship between the course and work demands. As well as changes in existing relationships a new one is being created. Within this relationship, there is a danger of rivalry and ‘splitting’, with the student/worker, course, and workplace becoming polarized. For instance, one is all ‘good’ and the other all ‘bad’.

h) It may help contain these potential difficulties if the course and workplace enter into direct communication so that a relationship with some understanding of each other’s needs can develop.

i) The pressure on the Community and myself to undertake training, alongside the partial nature of my absence, contributed to the use of denial as a defence against anxiety. Given the difficulties that were involved in my absence, there was good reason to unconsciously deny the extent of them and to underestimate the impact on all of us. This denial, paradoxically, probably contributed to the difficulties being greater than they might have been.

Working Through the Initial Difficulties

Springfield continued to be uncontained during the first three months of my absences. Three boys who were particularly uncontained and behaving dangerously were excluded from the community. Two members of staff also left, one in a fairly planned manner, one suddenly. The anxiety involved in this situation was extensive. This led to the involvement of the Community’s management consultant in helping us identify how we might improve the situation.

It seemed clear that my part-time absence was intolerable for staff and boys. It was agreed by myself, the deputy, the Principal, and the management consultant, that it may be better for me to be more clearly absent in a block of three days plus one other day in the week and that the deputy should have complete responsibility for the day to day running of the household. This would include representing the household within the Community and externally and chairing team meetings. The management consultant suggested that I take the role of ‘chairman’ responsible for policy and the deputy the role of ‘chief executive’ responsible for day-to-day management. I would act as ‘deputy chief executive’ to cover the deputy’s time off. This was largely due to there not being anyone else on the team ready to take this responsibility. We agreed that I would formally hand over these responsibilities in a team meeting.

One of the main intentions of this change was to reduce my importance as a ‘father figure’ and to strengthen the presence of a ‘father figure’ in the household, by transferring the authority and responsibility to the deputy. By making my absence more clear, this change also made it more difficult for all of us to deny the reality of the change.

During the weeks and months after this change, the problems with uncontainment continued. Throughout this period frequent references were made by the boys, staff team, and senior management along the lines that Springfield had two ‘fathers’. The boys argued as to who was the best or worst manager, the staff team kept referring to the two ‘father’ structure. A senior manager asked who was running Springfield, myself or the deputy.

The extent of these difficulties necessitated ‘crisis’ meetings between myself and the deputy, the two of us with senior management, and all of us with the management consultant. The original idea of the new model was that the deputy would be the more central ‘father figure’ acting as a ‘container’ for staff and boys, with myself more distant, keeping an overview of the household and acting as a ‘container’ for the deputy. Part of what needed containing in this situation was unresolved feelings connected to the relationships boys and staff have had with previous ‘father figures’ in their lives. The ‘father figure’ acts as a figure onto whom these feelings may be transferred. In turn, he/she will have a counter-transference towards the staff and boys. Through the process of containment, these feelings can be ‘held’, processed, understood, and eventually integrated. This process may potentially enable the ‘father figure’, staff, and boys to evolve and develop as individuals.

After considerable analysis of the difficulties experienced in Springfield during the first year of my absence, the management consultant suggested that we had a problem of ‘split transference’ projected onto myself and the deputy. Partly because of the uncontained situation and anxiety connected to this, I had not been able to achieve the distance in my role as ‘chairman’. Instead of having one ‘father figure’, we had two, which led to a split in the Kleinian (Ogden, 1983) sense between myself and the deputy, with a ‘good father’ transference onto one and a ‘bad father’ onto the other. This was very difficult for us both to work with and unhelpful for boys and grown-ups, creating the opportunity for difficult feelings to be “split off’ into one of us or the other. Communication between us and acknowledgement of what was happening did help at times. However, our feelings of rivalry and competitiveness made this very difficult. On occasions we used a third party, such as a consultant, to help us work on our relationship. This still did not help us sufficiently and the conflict between us grew, confusing the areas of responsibility that had been worked out.

The following factors may have contributed to the difficulties developing rather than subsiding:

a) The leadership model was different than any previously used in the Community. During the difficulties in Springfield, it was hard for the senior management to allow me to become more distant. I felt pressure on me to take charge and ‘sort things out’.

b) The change involved considerable letting go of my responsibility in Springfield. The loss involved in this may have added to the resistance to taking on a new role.

c) The envy towards me continued and may have been strengthened by the management consultant recommending I take on a more ‘distant’ role. At one point during this stage, when Springfield was being focused on as the household with the most serious difficulties and the cause of difficulties in other households through the boys' disruptive behaviour, the management consultant suggested that Springfield was under an envious attack from the Community in connection with me being on the course.

d) The absent person needs to think carefully about his/her feelings in response to envy. If the person feels guilty about his/her absence, he/she may accept the ‘envious attack’ and ‘spoil’ the situation by leaving the course for instance. Envy needs to be acknowledged and talked about.

e) The deputy and I were both male ‘father figures’ probably reinforcing the likelihood of a ‘split transference’. This is particularly difficult to work with, as it reflects the primitive splitting connected with the earliest relationship, where the infant is not emotionally able to feel love and hate towards the same person.

f) The staff team was ‘unheld’, partly because of a lack of another experienced person in the team who could work with the task of facilitating a more appropriate ‘holding environment’ for staff (Miller, 1993a) alongside the supervision work of the deputy.

g) Taking on the role of deputy ‘chief executive’ continued to give staff and boys a direct opportunity to relate to me as a ‘father figure’. This strengthened the possibility of ‘splitting’ and made it difficult for me to achieve the ‘distance’ necessary in my role as ‘chairman’.

The Resolution of the ‘Crisis’

When the management consultant suggested that we had a problem with ‘split transference’, he also pointed out that because of our management structure, this problem was inevitable to some degree and it was unlikely that we could return to ‘normal’. It seemed to me at this point, that myself, the deputy, and senior management, were able to accept the loss of how things used to be, and rather than deny this by trying to get things back to ‘normal’, we had to find a way of living with the problem and evolve from there.

From the beginning we had been using an “assumption of ordinariness as a denial mechanism” (Trist et al, 1963). Trist et al, whilst consulting to the National Coal Board, attempting to introduce a new form of work organisation in one of their collieries, made a similar discovery. After a prolonged period of difficulty, they claimed (p.496),

Those concerned were using the idea of ordinariness as a means of psychological defence against elements in the situation they were unwilling to confront. The principal effect was that the panel was treated as a production unit under difficulties, rather than perceived for what it was—a training and development project working under the stress of a demand for full production.

This realization and acceptance of it took the pressure off me and the deputy to some extent, in that it offered a hypothesis of why we were ‘failing’, that was not based on our professional competence. This in itself reduced the tension around our situation and improved the level of containment in Springfield.

It was agreed by myself, the deputy, the Principal, and the management consultant that l should hand over my role as deputy ‘chief executive’ to someone else in the team and take on a new role in a more ‘maternal’ capacity, meeting staff individually, attempting to improve the quality of ‘holding’ for the staff.

The management consultant also suggested that my taking on this more ‘maternal’ role may reduce the tendency for myself and the deputy to be seen as two ‘father figures’, and hence reduce the split transference. I relinquished my role as a ‘father figure’ in direct work with staff and boys. I retained my leadership role of the deputy by managing the household policy boundary.

This change had a considerable impact. References to the two ‘father’ model were made much less frequently. The boys told me I was no longer the manager. New members of staff said they related to me in my new role and not as a manager. Staff were able to use their meetings with me productively. The senior management expressed less conflict as to who was in charge and upgraded the deputy’s salary to reflect the increase in his responsibility. However, this new model still had its difficulties. Managing the boundaries between my two roles required very careful work. On the whole, this has been successful with my role and that of the deputy complementing each other.

Throughout this process of change, the role of the management consultant was vital in enabling the difficulties involved to be contained. Miller (1993, p.232) claims,

... sustained change cannot be localised within the system most directly affected: changes must also be brought about in the relationship between the system and the environment in which it operates.

And,

In order to achieve such transformations, one or preferably both of two conditions seem to be necessary. The first is the operation of a sanctioning authority which straddles both the system concerned and the relevant authority. The second I shall call ‘consultancy’.

In my case Springfield was the system most directly affected, the community the environment, and also the authority. The management consultant helped facilitate the changes that were necessary in the relationship between Springfield and the Community if my ‘absence’ was to be managed successfully.

Co-leadership

It seems that over a while we had moved towards a management model similar in some ways to co-leadership. If a leader is going to be absent for significant periods a move towards co-leadership may be necessary to ensure continuity of leadership. This model of leadership has a dynamic that is different from singular leadership, highlighted in our case by the ‘split transference’. If a model of co-leadership is going to be entered into, it is worth being aware of the potential advantages and disadvantages. My experience in Springfield has highlighted some of them. Research carried out by co-therapists, co¬leading different treatment groups, has helped me understand my own experience.

Quite often in my relationship with the deputy, there has been a competitive and rivalrous tension between us. This was picked up by the staff and boys. On one occasion during the early period, after an interchange between us, a group of boys started chanting ‘that told you’ towards the deputy. Some of the boys became quite panicky. On another occasion, a staff member said if we argued it felt like we were quarrelling parents. If the boundaries of each other’s roles are clear and both are in touch with their competitive rivalrous feelings, it is possible to work through these difficulties. On the whole, we have been able to do this, providing staff and boys with a positive model of how conflict can be worked through by two people, that on a transference level may represent mother and father, father and son, two parents or two siblings.

However, at times these difficulties have been so great that we have needed assistance from a consultant or other external person. Cividini-Stranic and Klain (1984, p.158) describe how supervision is necessary to avoid the toxic effects of conflict between the co-leaders, which may result in open or more dangerously, defensive intolerance between them.

If there is not an overtly rivalrous or competitive relationship between the two leaders, there may be the problem of envy of the two leaders due to their perceived closeness. Skynner (1974) recognises the difficulties in this situation but also claims that if envy can be recognised it is a powerful force for growth and change.

Envy has played its part in the relationship between us. The deputy, for the first year, was on a considerably smaller salary than myself and frequently expressed his dissatisfaction with this.

Status differentials often result in tension and unclarity about the leadership role for both therapists and patients (Yalom, 1975, p.420).

The upgrading of the deputy’s salary reduced this difficulty. A difficulty for me has been letting go of the closeness to the work situation that I previously had and allowing the deputy to move into that space.

Another potential difficulty for co-leadership is that of ‘pairing’ (Bion, 1962). Bion describes how a group may unconsciously create a pairing, whom it will be hoped can produce an answer to their difficulties. This dynamic may push the pair together in an atmosphere of hopeful expectation, which may lead to collusion that would undermine the work task. This did not seem to be an underlying dynamic in our situation.

A difficulty we have experienced more often has been a reluctance to let ourselves work uninhibitedly, for fear of ‘outdoing’ or undermining the other. “In the presence of a co-therapist, he may experience his narcissistic needs as a problem because he may feel the urge to show off before his colleague. Therefore, the control of narcissistic needs and vulnerabilities must be stricter, which necessarily affects the therapist’s professional self’ (Cividini-Stranic and Klain, 1984, p. 158). While this has caused some difficulties in our leadership, Cividini-Stranic and Klain point out (p.158) on the positive side that,

It gives an opportunity to practice how to endure control, to expand his knowledge of his own self, and to strengthen his tolerance to the libidinous and aggressive manifestation of the other therapist in the dynamic of the group as a whole.

As well as the development in our self-understanding brought about by working through these narcissistic frustrations, the inhibition of myself and the deputy has at times created the space for other staff to express themselves more constructively, rather than be dependent on the ‘all-knowing’ leader. The co-leadership may also offer the opportunity for mutual observation of each other, resulting in constructive feedback. Leadership may be more open and sensitive having this dual perspective and perception.

The relationship between the deputy and myself in terms of experience and role, has also been of significance and has had different dynamics at different times. Initially, I was by far the more experienced worker. This gave the deputy something to gain from working with me and myself the task of training him. While this may have reduced the potential rivalry between us, it competed for the attention that I could give to the rest of the staff and boys. As the deputy’s experience has grown with time, his dependence on me has decreased, enabling me to give more attention to staff and boys, but leading to an increase in rivalry between us that has sometimes impinged upon this attention.

As discussed earlier, the similarity in our roles was probably unhelpful and did not provide a sense of mutual interdependence or benefit from each other. When I changed my role to the more ‘maternal’ role this situation improved considerably. Salvendy (1985, p. 139) claims,

Present indications from practice and theory point out the best constellation in co-therapy is given when the co-leaders are of opposite sex, of different professional disciplines and of equal status.

Bloomfield, (1987) claimed that a male-female pairing made it easier for the ‘group’ to see itself as a family in which earlier experiences could be re-experienced and re-enacted.

Bales (1953) describes how the co-leader roles may be divided into two types of leader, the task-executive leader, spurring the group on to perform its primary task, and the social-emotional leader, who attends to the group’s emotional needs, reducing conflict difficulty to allow the group to continue. This is effectively how the deputy and myself eventually divided our roles.

Whatever the particular relationship of the co-leaders, it is the working through of the feelings involved in that relationship that is ultimately of most value in a treatment setting. If the leader’s absence necessitates a form of ‘co-leadership’, and if the potential dynamics of that relationship can be anticipated to some extent, co-leadership may be planned in a manner that is of potential benefit to the staff and client group, in performing their primary task. For instance, if the client group has a strong tendency towards ‘splitting’ co-leadership can be very problematic. However, if this is anticipated and resources can be prepared to work with the problem, co-leadership may be a useful tool in healing the ‘split’.

Ending of the Absence

At this point, I have been on the course for just over one and a half years. The staff and boy group are more contained than at any previous stage with clear progress being made in the treatment of the majority of boys and the development of staff.

At the time of writing, I have three more months of the course before being able to return to full-time work. This is a potentially very problematic stage of the absence. It would be very difficult for myself and the deputy to return to our previous positions. The loss involved in the change for both of us would be considerable, with the potential accentuation and repetition of many of the difficulties already experienced.

I am sure that if the absence has been covered for any period, giving or taking back responsibility is potentially problematic. If the period of absence is nearly two years it may be virtually impossible. The deputy and I have both evolved, not just over time, but out of the situation that has unfolded and the demands it has placed upon us to change. Whatever changes take place at the end of the absence will need to take account of and utilize the changes that have taken place during the absence.

At present there is a proposed plan for the deputy to become learn leader of Springfield and myself to take on a more senior role in the Community.

Summary

I have written this essay from the perspective of my own experience of absence. However, I would argue that the themes I have drawn attention to may be relevant to absence in general, and parallels may be drawn in many different situations where absence needs managing. I shall summarize what I consider to be the most significant themes.

The part-time absence of the leader is a significant event and potentially a major change. Strong feelings may be aroused in all those involved with the absence, with feelings of envy particularly likely in these circumstances. As the absence is likely to bring about changes for all involved, potential difficulties must be anticipated and communication encouraged. This should continue throughout the absence. In the case of absence for training, it may also be important for there to be communication between the ‘training body’ and workplace. The course and workplace are both places where I have been able to work on the issues of my absence, and both have played an important part in working through the difficulties.

The nature of part-time absence may strengthen the likelihood of denial being used as a defence against the anxieties involved. This may mean the difficulties are greater than expected and communication needs hard work.

On a practical level, the absence needs to be covered adequately so that those working with it are not left struggling. On a more complex level, covering the absent leader’s role may require some changes in roles, depending on the implications the absence has for the ‘task’ of the setting. If this is the case, the changes need to be worked on carefully, ensuring that they are appropriate for the task, clearly defined, and including formal changes in status where appropriate. A significant absence of the leader may lead to a form of co-leadership. If this is the case then the dynamics of co-leadership need careful consideration, so that the most appropriate form and conditions can be developed for the particular setting. The communication between the absentee and the person covering his/her role is an essential factor in managing the absence.

The ending of the absence may be complicated and will need careful consideration. In all of these areas the assistance of a consultant or ‘sanctioning authority’ can play a vital role in enabling the absence to be worked with productively. In many cases, this may be essential.

If all those involved with the absence, the absentee, the staff group, the client group, and the wider organization, have some investment in the absence and are likely to benefit from it, then it is more likely to be managed effectively, with each taking the responsibility for managing their part connected to the absence. Rather than one ‘party’ being responsible for managing the absence, the relationships between all concerned will need working on if the difficulties are to be resolved.

The absence needs to be potentially compatible with the task of the setting. If there is the commitment and necessary resources available to work with the situation, then in many cases the difficulties encountered in managing absence, have in them the potential for learning and growth for all those involved.

REFERENCES

Tomlinson, P. (1995) The Leader’s Part-Time Absence: Difficulties and Attempted Resolutions in a Residential Child Care Setting, in, Therapeutic Communities: The International Journal for Therapeutic and Supportive Organizations, Vol. 16, No. 5

Bion, W. (1962) Learning from Experience, London: Karnac

Bloomfield, I. (1987) Co Therapists Group at University, College Hospital, in, Group Analysis Vol. 20 no. 4, 319-331, Sage Publications

Cividini-Stranic, E. and Klain, E. (1984) Advantages and Disadvantages of Co-Therapy, in, Group Analysis, XVIII2, 156-159, Harold Behr: London

Dockar Drysdale, B. (1990) The Provision of Primary Experiences: Winnicottian Work with Children and Adolescents, Free Association Books: London

Menzies-Lythe, I. (1979) Staff Support Systems: Task and Anti-Task in Adolescent Institutions, in, Containing Anxiety in Institutions (1988), London: Free Association Books

Miller, E. J. (1986) Dedication and Charisma: Eric J. Miller Offers an Appreciation of Richard William Balbernie, who Died Recently, in, Therapeutic Communities: International Journal of Therapeutic Communities, 32, 4, Winter 2011, https://www.johnwhitwell.co.uk/child-care-scrapbook/richard-balbernie/

Miller, E.J. (1989) Towards an Organizational Model for the Residential Treatment of Adolescents, London: Tavistock Publications

Miller, E.J. (1993, a) Creating a Holding Environment: Conditions for Psychological Security, The Tavistock Institute

Miller, E.J. (1993) From Dependency to Autonomy, Free Association Books: London

Ogden, T.H. (1983) The Concept of Internal Object Relations, in, International Journal of Psycho-analysis, 64, 227-2241

Salvendy, J.T. (1985) Training, Leadership and Group composition: A Review of the Crucial Variable, in, Group Analysis, XVIII/2: 132-141. Harold Behr: London

Skynner, R. (1974) in, Pontalti, C., Report on Dr and Mrs Skynner’s Seminar, Rome 1973, followed by comment from Dr Skynner, in, Group Analysis, XII, 34-40

Trist, E., Higgin, G., Murray, H. and Pollock, A. (1963) The Assumption of Ordinariness as a Denial Mechanism, in, The Social Engagement of Social Science (1990), Free Association Books: London.

Whitwell, J. (1989) The Residential Treatment of Unintegrated Children, in, The Journal of the British Association for Counselling, No. 68: 21-28, https://www.johnwhitwell.co.uk/about-the-cotswold-community/the-residential-treatment-of-unintegrated-children-implications-for-therapeutic-communities/

Whitwell, J. (1994) Staying Alive: Is There a Future for Long Term Psychotherapeutic Child Care?, in, Therapeutic Communities, Vol. 15, No. 2: 87-97, https://www.johnwhitwell.co.uk/about-the-cotswold-community/staying-aline-is-there-a-future-for-long-term-pyschotherapeutic-child-care/

Wills, W.D. (1971) Spare the Child: The Story of an Experimental Approved School, Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England: Penguin Books

Winnicott, D.W. (1956) Primary Maternal Pre-Occupation, in, Through Paediatrics to Psycho- analysis (1958), Tavistock Publications: London

Winnicott, D.W. (1988) Human Nature, Free Association Books: London

Yalom, I.D. (1975) The Theory and Practice of Group Psychotherapy, New York: Basic Books Inc.

Files

Please leave a comment

Next Steps - If you have a question please use the button below. If you would like to find out more

or discuss a particular requirement with Patrick, please book a free exploratory meeting

Ask a question or

Book a free meeting