THE APPLICATION OF OPEN SYSTEMS THEORY TO HELP UNDERSTAND AND MANAGE DIFFICULTIES IN A PROCESS OF ORGANIZATIONAL CHANGE - PATRICK TOMLINSON (2025)

Date added: 12/12/23

Download a Free PDF of this Article

This paper was originally written as a piece of coursework when I was studying for a Postgraduate Certificate in Strategic Social Care Leadership at Birmingham University in England. I have revised it and shared it as it contains some concepts that continue to be useful.

Introduction

Using my place of work, TCS Care (an organization in England that provides residential care and psychodynamic treatment for children traumatized by severe abuse and neglect) as an example, I will describe the nature of the organization as a whole system, the nature of its internal dynamics, and its relationship to the external environment.

I will look at this during a period of organizational expansion, where after ten years of operating in one region of England the organization developed a second region. I will apply an open systems theoretical model and critique the usefulness of this. I will particularly focus on the process of boundary management concerning the primary task of the organization. Finally, I will give an example of a strategic intervention from the perspective of my role as a Director within the organization, using a systemic approach, and evaluate the effectiveness of this.

TCS Care

TCS Care began operating in the 1990’s providing therapeutic residential care and therapy for children severely traumatized by abuse and neglect. These children were some of the most damaged and vulnerable in the care system and required intensive and prolonged treatment to heal and make a recovery. The children were placed in children’s homes of up to 5 children. The children are placed with TCS by Local Government Authorities and stay on average for three years. Due to the severe nature of the child’s disturbance, the work is challenging and requires a high level of containment to deal with the anxieties involved.

After 10 years of operation, TCS had established an extensive service with over 10 children’s homes clustered around a 10-mile radius. At this point, TCS had sufficient demand for its service and decided it would be in the long-term interest to expand and develop its service into a 2nd region.

TCS as an Open System

The biologist von Bertalanffy (1950, 1950a) formulated the idea that organisms, human beings, organizations, and societies are open systems. He applied an evolutionary model of the dynamic interactive relationship between an organism and its environment to organizations. Classical organizational models were primarily closed physical systems, mechanically self-sufficient, neither importing nor exporting. Under the open systems model, an organization is in continual interaction with its task and the external environment. The organization can transform material or input but is also subject to potential change through this process. Miller and Rice (1967) as well as other team members of The Tavistock Institute of Human Relations further developed these ideas.

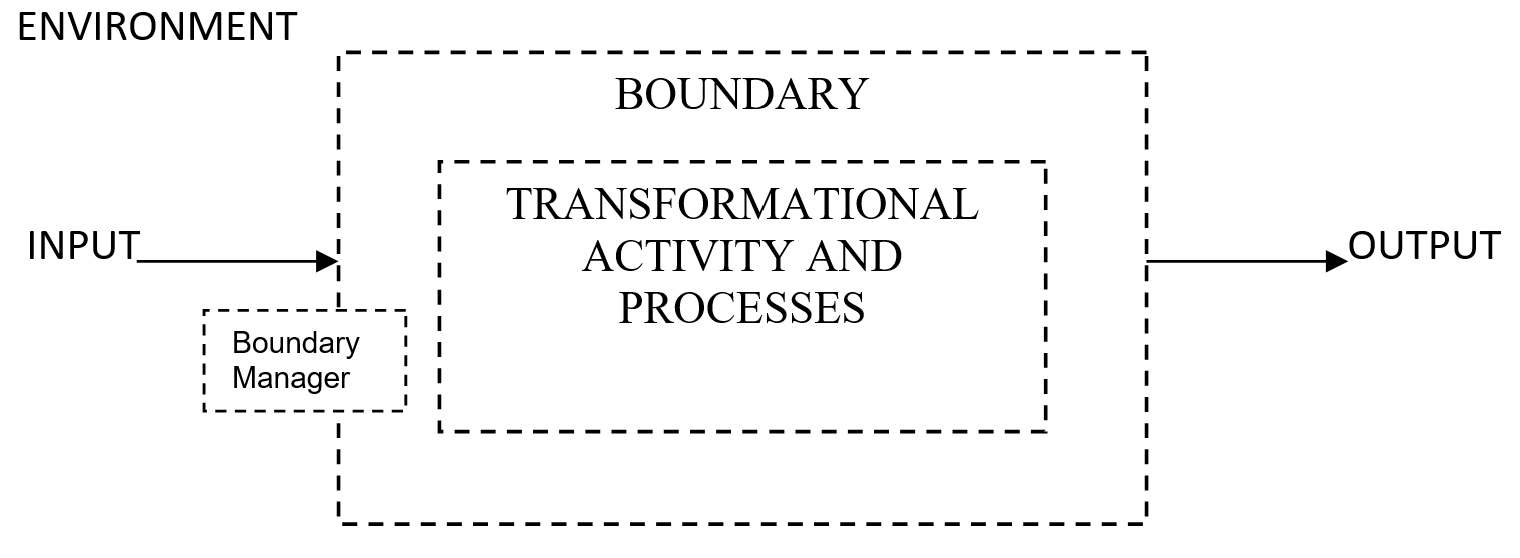

An organization is described as a system or a set of activities with a boundary and a purpose. The purpose of the organization or the activity it must perform to survive effectively is defined as its primary task (Rice, 1963, p.17; Miller and Rice, 1967, p.25). For example, the primary task of an organization that produces steel from iron ore is steel manufacture. Iron ore is the input, the raw material taken into the organization, across its boundary. Following transformational activity within the organization, the input is converted to an output, steel, and leaves the organization across its boundary. Using this simple example, it is apparent that the management of the boundary is critical to the organization’s success and survival. If low-quality iron ore is taken into the organization, the output may be too poor, and if too much poor-quality output is allowed out, business may decline rapidly.

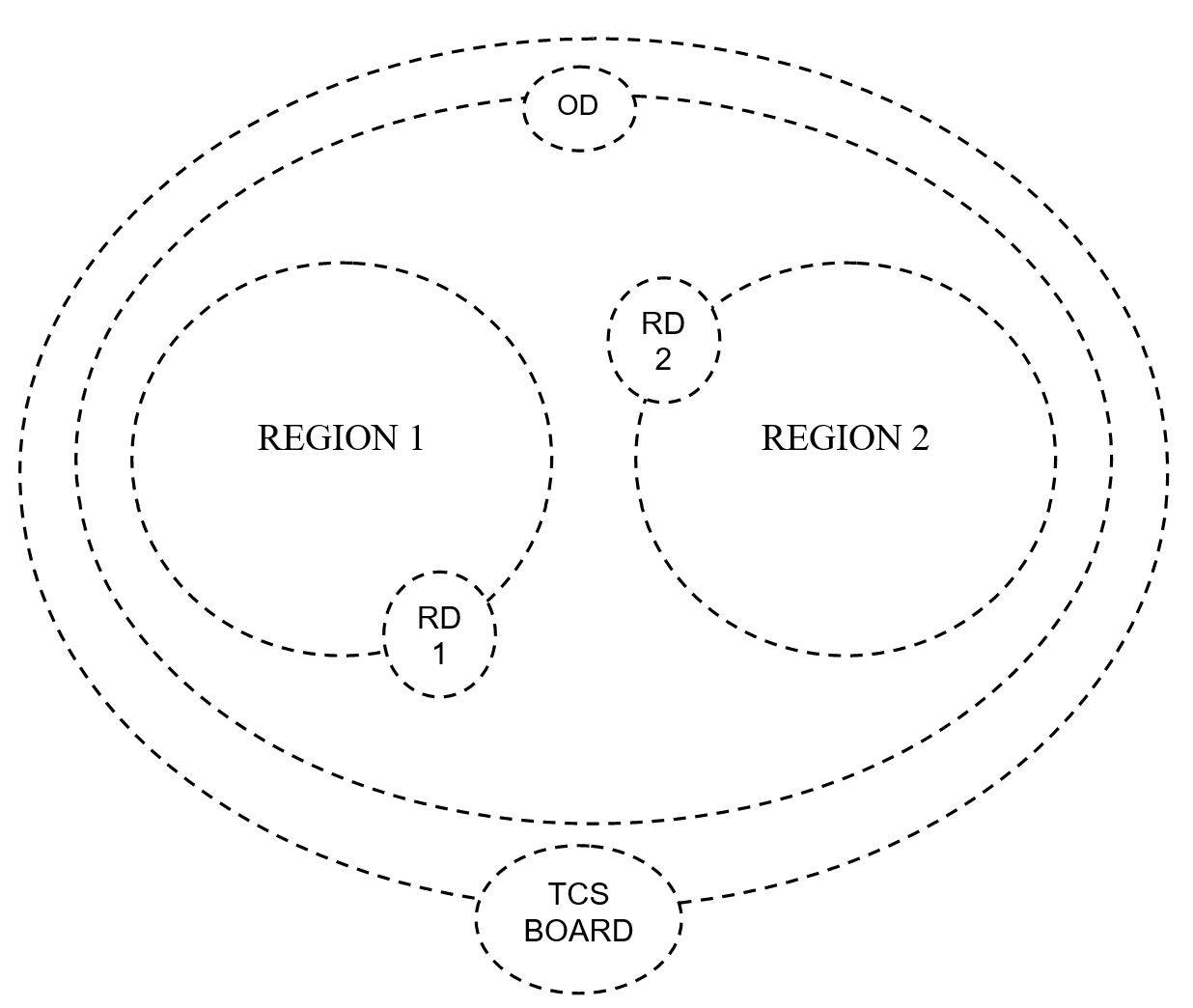

In an open system, the boundary is permeable, represented by the dashed line (see Diagram 1). There is a controlled flow of material, resources, and information across the boundary. The degree of permeability and control on the boundary will be determined by the nature of the primary task but is also changed by external developments. For example, the growth of the Internet has greatly increased the flow of information. The ‘boundary manager’ or system of boundary management is placed on the boundary of the organization so that both the inside and outside are observed and the relationship between the two can be regulated appropriately.

Diagram 1

Using this model, at TCS, the inputs are traumatized children, the activity and processes are therapeutic care, and the outputs are recovered children. The primary task of TCS is ‘healing traumatized children’. TCS has defined exactly what it means by healing so that there is no ambiguity on this point. Again, the critical nature of boundary management is apparent; if the wrong children are taken in, they may not be treatable, which could have serious consequences for all involved. If children are allowed to leave before they are sufficiently healed, TCS will not be achieving its primary task. If children are not allowed to leave when they have healed, they may regress.

Complexity of the System

The same model can also be applied to the departments or sub-systems within the organization. For example, at TCS, the two regions are sub-systems within the whole organization. Each region has its boundary which regulates its interactions with other sub-systems or departments within TCS. Each region manages transactions across its boundary with the external world of Local Government Authorities, etc, though this is done within parameters set by the whole organization. In this example, the boundary of the region is close to the boundary of the wider organization.

Within each region are various sub-systems, for example, Human Resources and Finance. The treatment approach also consists of three distinct sub-systems - Therapy, Education, and Residential Child Care. Each of the homes that the children live in can be seen as a distinct sub-system. All the sub-systems are interdependent and reliant on effective boundary management to work well together. The organization as a whole and its sub-systems need to be adaptive so that it can respond to changes in circumstances. Hence, a need for an appropriate degree of flexibility and permeability in its boundaries.

For example, if the age criteria for children placed in a particular home is changed from 7-14-year-olds to 7-11-year-olds, the boundary management of the home will be less flexible. The organizational boundary will need to adapt, in determining the age of children on admission. The human resources department may need to adapt, to ensure suitable staff enter the organization, and so on. Each of the sub-systems is committed to the primary task of the organization, though each will also have its sub-task. For example, the HR department’s sub-task may be to ensure that an adequate number of suitably qualified and experienced staff are recruited at the right time.

Normally, the sub-tasks are complementary to the primary task, though conflict can occur, and negotiation needs to take place across internal boundaries. An example in this area has occurred recently at TCS. Due to a clarification of our practice in healing traumatized children, additional training requirements are now demanded of staff, which means the standards of recruitment may need to be altered. This could create a challenge to HR in maintaining effectiveness in the performance of their sub-task.

As Miller (1967), has pointed out in his work on ‘Sentient Systems’, and as can be seen from my description of TCS, staff within the organization can belong to several different sub-systems at the same time. Staff may have differing levels of identification, attachment, and loyalty to the different parts of the system. For example, an HR manager may be most strongly identified with the organization, the region she works in, or her team. Many factors contribute to the complexity of the organization.

Boundary Management and the Therapeutic Task

It is important to note that boundary management has particular importance in residential services for children who have suffered trauma and other adversities. As discussed, open systems theory has shown how boundary management is generally relevant to organizational systems. In working with traumatized children, it is also a key part of the therapeutic process. The children have suffered the consequences of situations where boundaries were not appropriately in place. For example, where an adult was supposed to put a protective boundary in place but failed to do so, or where an adult crossed a boundary and abused the child.

Therefore, to recover and internalize a healthy boundary model and to establish their personal boundary they must experience clear and appropriate boundaries in their day-to-day life. Those who are closest to the child provide the model. However, the carers who work with a child will struggle to provide a healthy model if the whole organization they work within does not also have an appropriate boundary model. If boundaries are muddled in the organization, they will most likely become muddled in the work with the child.

Inherent in the issue of boundary management is the nature of authority. This is also always important - whose boundary, is it? Who has the authority on the boundary? Clear and appropriate authority is also vitally important in working with traumatized children. An authority that is exercised in the service of the task rather than one that is arbitrarily and inconsistently imposed.

Traumatized children are likely to act out their muddled sense of boundaries or act out because they have no boundaries. The impact of this can begin to confuse those working with the child and others throughout the organization. Holding boundaries safely and consistently is vital. Sometimes a child will test to find out if this can be managed. They will most likely have found out in the past that when tested, adults will become unable to hold boundaries and give up or react punitively. In this context, the testing of boundaries can be thought of as the search for safety. Bessel van der Kolk et al. (2007, p.424) explain clearly why this is so important in a trauma service,

Since interpersonal trauma tends to occur in contexts in which the rules are unclear, under circumstances that are secret, and in conditions where issues of responsibility are often murky, issues of rules, boundaries, contracts, and mutual responsibilities need to be clearly specified and adhered to (Kluft, 1990; Herman, 1992). Failure to attend strictly to these issues is likely to result in a recreation of aspects of the trauma itself in the therapeutic situation.

The organization consultant Isabel Menzies Lyth (1985, p.245) explains in her paper, The Development of the Self in Children In Institutions, how appropriate boundary management also supports the therapeutic task by helping develop a sense of identity,

It gives a stronger sense of belonging to what is inside, of there being something comprehensible to identify with, of there being ‘my place’, or ‘our place’, where ‘I’ belong and where ‘we’ belong together.

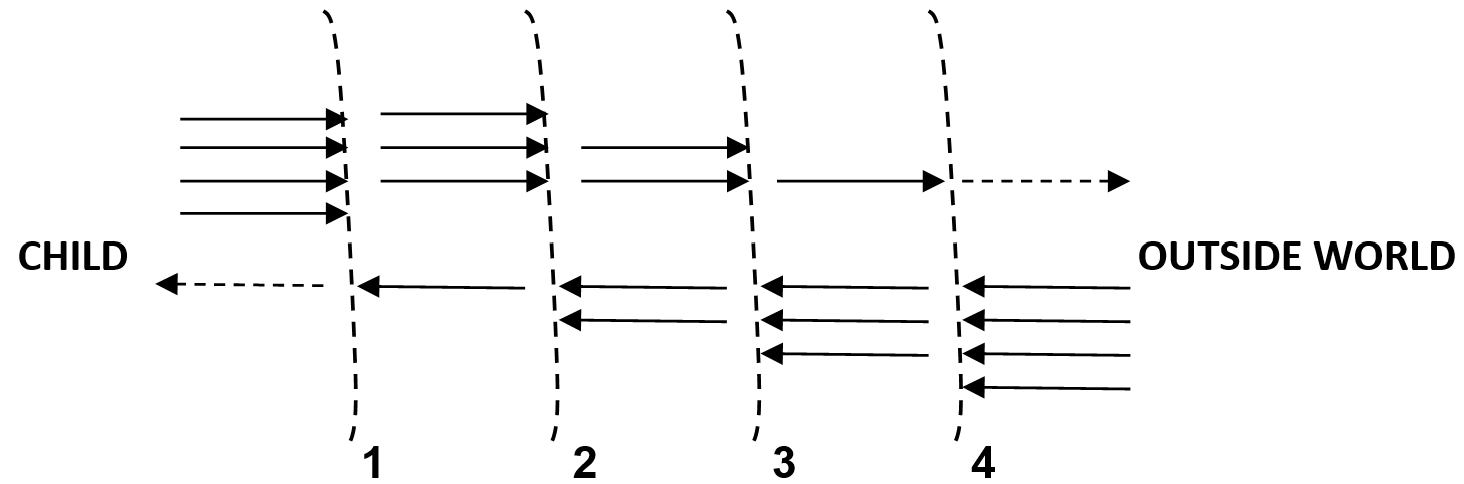

As well as the boundaries of the place, personal boundaries are also vital to healthy development and identity. In ordinary child development, there is always a balance between boundaries being too tight or too loose. Between the need for exposure and the need for protection. The parents and others manage the boundaries around the child. As the child develops, boundaries must continuously adapt to allow further development. Suitable boundaries for a 3-year-old are different than those for a 7-year-old. Applying this to a residential care setting, such as TCS, Miller (1989) has described the child as being in the centre of the organization with a series of permeable boundaries, or shock absorbers between him and the external world. For example, in this diagram, 1 could be the child’s Key Carer, 2 the Home Manager, 3 the Regional Director, and 4 a Senior Director.

Children who have been severely traumatized in their early years are in many ways like infants who need their relationship with the outside world to be carefully managed. Too much outside world and they can feel engulfed and too little, and they are the centre of the universe! They need protection from the outside world and the outside world from them.

Organizational Mirroring

My understanding of this is that through dynamic interaction with the primary task, aspects of the activity required to convert inputs into outputs will impact the organization and be mirrored throughout it. Conversely, aspects of the organization’s structure and culture will impact the primary task and be mirrored in the activity that takes place. This is also sometimes referred to as a parallel process.

Obholzer and Zagier Roberts (1994) describe this in consultancy work to a school that was experiencing problems with bullying between pupils. After a while, it was found that the headmaster was perceived as a bully and to be using bullying tactics to manage the staff. Once this was in the open and could be discussed within the staff group, reported bullying amongst pupils was significantly reduced. In this example, the organization's culture is impacted from the top down. This interfered with the transformational activity of teaching so that pupils learn.

At TCS it is also often the case that work with traumatized children has an impact upwards throughout the organization. Many of the children we work with have been sexually abused and this can have a particularly powerful impact on staff, systems, and the whole organization. Barton, et al. (p.179-180) argue,

Keeping the management of the organization on task with clear boundaries is by its very nature hugely difficult – partly because it keeps everyone in touch with the trauma we are working with. As described, appropriately clear management can be perceived to be harsh and abusive. When we are working with children who have been traumatized by abuse, and in particular sexual abuse, being clear about things is often responded to as if it is abusive.

Boundaries and roles in abusive scenarios are muddled and blurred – who is the adult and who the child? Therefore, in our work situation, an adult who is clear about her boundaries and stays appropriately in role is facing the abused child with the reality, that what happened was inappropriate. There is likely to be huge pressure to muddle this reality and blur boundaries. This will come from the children, those working directly with them, the organization, children’s workers, parents, and others, as the reality of abuse is painful with ramifications for everyone involved. This pressure will continually push itself into the organization so that, at all levels, there will be a tendency for things to become unclear and muddled.

Staff working directly with children can feel huge levels of anxiety about staying in their role and being clear in their work and boundary setting. There may be fear of potential reactions from children. For example, children may react as if the adult is an abuser. If this anxiety is not thought about, acknowledged, and understood it can be transferred up the system so that those in most senior positions can become increasingly unclear about their role and boundaries.

Menzies Lyth (1979) has described in detail the difficulty of maintaining boundaries and effective management, particularly in people-caring organizations. She warned of the danger of management structures being unduly influenced by therapy (p.230) and spoke of the high levels of preoccupation with the primary task that is necessary to remain on task (p.235).

Strategic Intervention

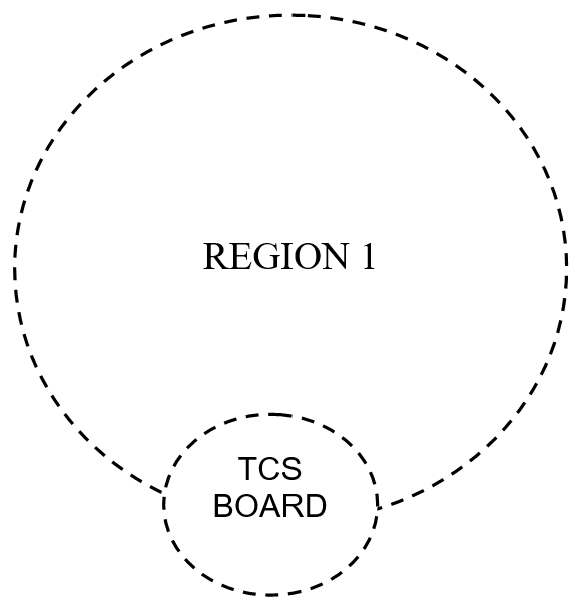

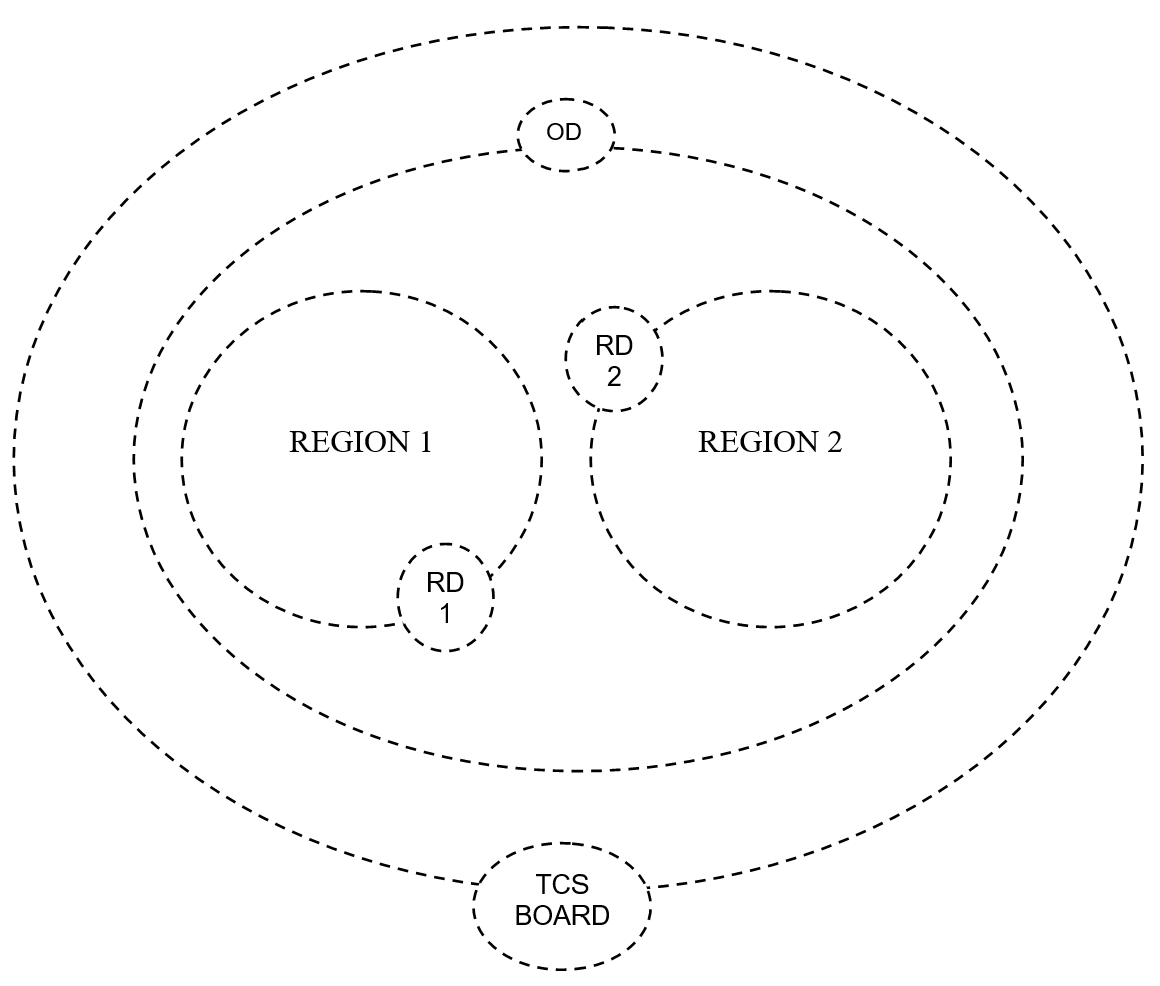

Around 3 years ago TCS began an expansion programme to develop a second regional location. Previously TCS had been based in just one region (Region 1 – see Diagram 2).

Diagram 2

The Board of Directors, four people had been directly managing Region 1 for the last ten years. The expansion required the Board to hand over the direct management of Region 1 so that it could move to a position on the boundary of the whole organization. This would support the strategic aim of ensuring that both regions are developed in a consistent manner working to the same model (see Diagram 3).

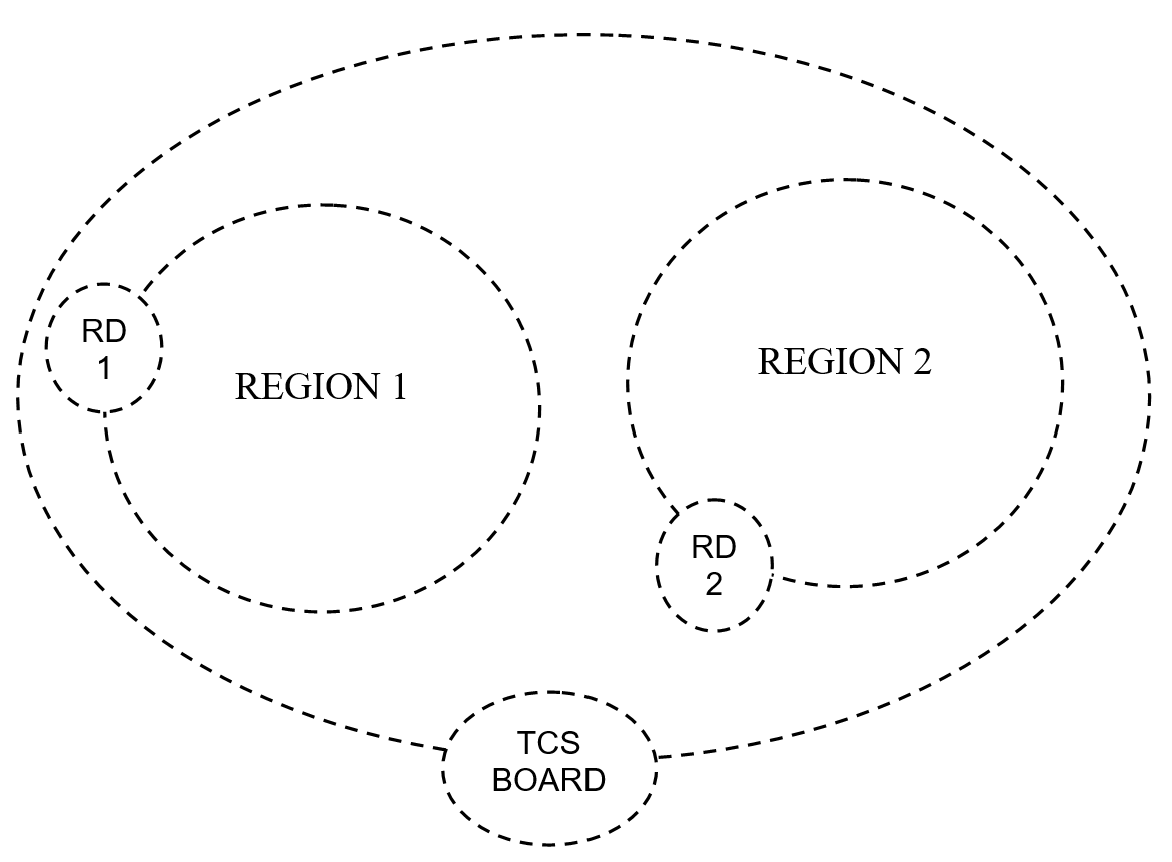

The Board of Directors, four people had been directly managing Region 1 for the last ten years. The expansion required the Board to hand over the direct management of Region 1 so that it could move to a position on the boundary of the whole organization. This would support the strategic aim of ensuring that both regions are developed in a consistent manner working to the same model (see Diagram 3).

Diagram 3

RD = Regional Director. Each Regional Director would have a senior management team. These two teams needed to be developed. We decided to develop the Region 1 team from existing personnel and recruit the Region 2 team. As can be seen from diagrams 2 and 3 the changes involved were significant. Deciding where to position the new boundaries was challenging. One of the biggest challenges was for the TCS Board to hand over Region 1, which it had been running since its beginning, to a regional management team and to create a new regional management team in Region 2.

Both teams would need the right degree of autonomy and direction, to function effectively whilst at the same time ensuring that Region 2 developed in line with the TCS model. If the Board sets its boundary too far from the regional boundaries this could be uncontaining and if too close, it could be stifling and overly restrictive. The consequences of either would be mirrored throughout the organization, potentially causing difficulties in task performance.

The potential for high levels of anxiety in both regions was at the same time increased due to the changes. Region 2 had the challenging task of starting from scratch. The security provided in this work, by having a history, shared experience, knowing each other, and having a culture, cannot be underestimated. Region 1 was faced with having to 'grow up' and be one of two regions, rather than the only one. The Board had to face the challenge of separating from Region 1 and letting go of their ‘baby’ while creating and giving birth to the new region. Once the plans were communicated these types of feelings quickly surfaced within the organization. As well as excitement there were many expressions of anxiety about the forthcoming change – such as fear that the new Region 2 would be a huge drain and burden, sucking up the resources of Region 1.

As we progressed and Region 2 opened its first two homes, we experienced major difficulties in both regions. Anxiety levels became extreme, especially in Region 2. There were many symptomatic problems such as high levels of staff sickness and turnover, serious difficulties in containing children, concerns from external inspectors, and placing authorities. At one point in Region 2, the police were called to an incident at one of the homes, and 2 children were arrested. The boundary of the Region 2 region had become too permeable so there was in effect no control – the police were called to impose a boundary and authority.

It is possible that due to the newness of the Region 2 management team, the authority within the region was undermined by the closeness of the TCS Board to the day-to-day operations. The TCS Managing Director had taken up the role of line managing the new Regional Director. It could also be argued that this was not a containing model. The Managing Director, positioned on the boundary of the whole organization, was at risk of losing his position by being drawn closely into the difficulties in Region 2, or of drawing Region 2 too much towards the boundary of the whole organization. Meanwhile, Region 1 became relatively unsupported.

Shortly following the police intervention, the Board agreed to put one of the senior Directors in charge of Region 2 for a period. This enabled the Managing Director to return more clearly to the ‘organization as a whole’ boundary. The aim was to strengthen boundaries and to contain anxieties more effectively. Though there were major difficulties to work through, Region 2 began to settle down and the symptomatic problems began to subside. Following this we decided to appoint one of the TCS Board members as Operational Director to both Regional Directors. This created an additional boundary between the regions, the TCS Board, and the outside world. Given the newness of the regional team and structures, the aim was to strengthen the level of containment offered by the organization (see Diagram 4).

Diagram 4

As the Operational Director (OD) settled into the role, both regions began to feel significantly more contained and on task. However, at this point, a further need for change became apparent. In the crisis period, the TCS Board had taken on a firefighting role and had become enmeshed with operational management. There was a reluctance of the Board to relinquish certain areas of responsibility to the regional operations. For example, the Board controlled the staff recruitment process and had tight control over budgets. The difficulty can be seen in Diagram 4, where the TCS Board and Operational Director, whilst physically separate, overlap in the same space. The separation process had begun, though there was a clear need to unravel previous ways of working, redefine boundaries, and clarify roles.

The regions began to find this blurring of boundaries, undermining their authority and capacity to manage effectively. Teams within both regions were expressing confusion as to who was responsible and accountable for which aspect of the task. It became clear that this situation would weaken the boundary control of the regions and begin to have a serious impact on containment within the regions. On working on this with the Board it was agreed that we would hold a workshop, with an external facilitator, to clarify the nature of the working relationship between the TCS Board and Regional Management Teams to help clarify roles and boundaries.

The workshop was attended by twelve senior staff from the Board and Regional Management teams. The workshop was a challenging event, though we were successful in making good progress towards our goal. Following this, the Board also agreed to changes, which helped to clarify boundaries and enable authority to be held more clearly in the appropriate roles. It was also agreed that progress would be reviewed every month. In the six months that followed, we experienced improved task performance in both regions, reflected in positive levels of progress for children, reduced staff sickness, and increased child placement levels. At the same time, the TCS Board was able to focus on strategic issues, leading to some significant new developments.

Diagram 5 shows the situation following the workshop, with more space between the boundary of the TCS Board and the boundaries of the Operational Director and the regions. The next challenge as the regions become increasingly established will be to find the appropriate degree of distance so that the regions can function with autonomy, whilst ensuring that they continue to work to the TCS model consistently. The regional boundaries are now more likely to become too impermeable, rather than too permeable.

Diagram 5

Conclusion

The open systems model provides an excellent framework for thinking about and understanding the nature of organizations, in terms of the primary task, boundaries, roles, and authority. From this perspective, we are then better able to make effective interventions that are in service of the primary task.

The model demonstrates how an organization is a dynamic entity, inter-relating across its external and internal boundaries. Changes in any one part will have an impact on the others. There are other important aspects of the theoretical model on organizational dynamics and resistance to change, which I have not explored here, such as, ‘The Functioning of Social Systems as a Defence Against Anxiety’ (Menzies Lyth, 1959) and ‘Basic Assumptions’ (Bion, 1961).

The example at TCS shows powerfully how, when one part of the organization changes, all other parts will also be affected and change in some way. This is a dynamic process and the exact nature of how things will change is difficult to anticipate. By highlighting the dynamic and interrelated aspects of organizations, it is clear that leadership using this model must be able to tolerate uncertainty.

Rather than provide a blueprint for how to lead an organization, it provides a framework for thinking about what is happening, drawing a hypothesis, and testing this through planned interventions. On the one hand, this may be seen as a weakness, lacking in clarity and direction. In my view, in today’s environment of increasing unpredictability and uncertainty an approach that embraces this reality is a healthy one.

However, given the complexity of a situation such as I have described, we may have benefited from a process of external consultancy – offering an independent eye looking in to see things that those in the group are unaware of. As Miller (1993, p.7) has described the consultant working with an organization undergoing significant change can also help to contain anxieties so that those directly involved are better able to see, think about, and tackle the difficulties.

There was a shared recognition that both individuals and groups develop mechanisms to give meaning to their existence and to defend themselves from fear and uncertainty; that these defences, often unconscious and deeply rooted, are threatened by change; and that consequently it is an important aspect of the professional role (consultant) to serve as a container during the ‘working through’ of change, so as to tackle not only the overt problem but also the underlying difficulties.

There may also be a benefit in combining open systems theory with a focus on matters related to individual performance, such as personality profiling. Open systems theory can be perceived to explain everything in terms of the organizational dynamic, avoiding matters related to individual performance and competence. Similarly, it could be argued that open systems theory underplays the significance of underlying political influences. For example, in the change from Diagram 2 to 3, it could be argued that the Operational Director has achieved considerable power by replacing the Managing Director. From the open systems perspective, the key question is whether the change is in the service of the task.

The open systems model encourages the development of a thinking organization. This mirrors the task of enabling traumatized children to heal, where restoring or establishing the capacity to think is a key therapeutic aim (Tomlinson, 2005). Effective application of an open systems model has the potential to establish a culture that is most compatible with the primary task.

References

Barton, S., Gonzalez, R. and Tomlinson, P. (2012) Therapeutic Residential Care for Children and Young People: An Attachment and Trauma-informed Model for Practice, London and Philadelphia: Jessica Kingsley Publishers

Bertalanffy, L. von (1950) The Theory of Open Systems in Physics and Biology, in, Science, 3:23-N

Bertalanffy, L. von (1950a) An Outline of General System Theory, in, British Journal of the Philosophy of Science, 1:134-65

Bion, W.R. (1961) Experiences in Groups, London: Tavistock

Herman, J.L. (1992) Trauma and Recovery, New York: Basic Books

Kluft, R. (1990) Incest-Related Syndromes of Adult Psychopathology, Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press

Menzies Lyth, I. (1959) The Functioning of Social Systems as a Defence Against Anxiety’ in, Containing Anxiety in Institutions (1988), London: Free Association Books

Menzies Lyth, I. (1979) Staff Support Systems: Task and Anti-Task in Adolescent Institutions, in, Containing Anxiety in Institutions (1988), London: Free Association Books

Menzies Lyth, I. (1985) The Development of the Self in Children in Institutions, in, Menzies Lyth, I. (1988), Containing Anxiety in Institutions: Selected Essays, Volume 1, London: Free Association Books

Miller, E.J. and Rice, A.K. (1967) Systems of Organization: The Control of Task and Sentient Boundaries, London: Tavistock Publications

Miller, E.J. (1989) Towards an Organizational Model for Residential Treatment of Adolescents, Unpublished paper

Miller, E.J. (1993) From Dependency to Autonomy, London: Free Association Books

Obholzer, A. and Zagier Roberts, V. (1994) ‘The Troublesome Individual and the Troubled Organization’, in, Obholzer, A. and Zagier Roberts, V. (Eds) The Unconscious at Work: Individual and Organisational Stress in the Human Services, London and New York: Routledge

Rice, A.K. (1963) The Enterprise and its Environment, London: Tavistock Publications

Tomlinson, P. (2005) The Capacity to Think: Why it is Important and What Makes it Difficult in Work With Traumatised Children, in, Therapeutic Communities, Vol. 26 No. 1, pp.41-53

Van der Kolk, B.A., McFarlane, A.C. and Van der Hart, O. (2007) A General Approach to Treatment of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, in, Van der Kolk, B. A., McFarlane, A. C. and Weisaeth, L. (eds.) Traumatic Stress: The Effects of Overwhelming Experience on Mind, Body and Society, New York: Guilford Press

Files

Please leave a comment

Next Steps - If you have a question please use the button below. If you would like to find out more

or discuss a particular requirement with Patrick, please book a free exploratory meeting

Ask a question or

Book a free meeting