1-1 LINE MANAGER-DIRECT REPORT MEETINGS IN COMPLEX, EMOTIONAL AND RELATIONAL, HIGH-RISK WORK - PATRICK TOMLINSON (2024)

Date added: 25/09/24

Download a Free PDF of this Article

INTRODUCTION

While I use the terms complex, emotional & relational, and high-risk work in the title, much of this article is relevant to any kind of work and occupation.

In 1985 I began working in the field of therapeutic residential care for young people children who had suffered trauma and other adversities. These traumas and adversities had a major effect on their development. This is sometimes referred to as developmental trauma (Van der Kolk, 2005). Our task was to care for and through a therapeutic approach enable young people to recover from their adversities and resume healthy development. The work we were involved in was complex, challenging, and sometimes extremely difficult to understand. It was emotional as well as intellectually demanding work. I soon experienced the vital processes that provide support, learning, and development opportunities for the staff.

This article aims to discuss the general value of a 1-1 meeting process between a manager and their direct reports. Typically, this process in my field of work is called supervision. That is a common term in the UK and Ireland and some other countries and professions. However, I have found that in the USA the term 1-1 is often used to mean a similar thing. I found this a little unusual, to begin with. It sounded a bit informal like a catch-up, but I have found that the purpose and task are usually clear.

The use of the term 1-1 has made me wonder about the word supervision and whether it is always helpful or not. Does it set the right tone for the process? The same word is also used for ‘watching over’ children, i.e. parental supervision. Once when a new person was joining my team, I explained that I would have a supervision meeting with her every few weeks. She seemed surprised so I asked her what she felt about it. She said that she was offended and didn’t expect me to think she didn’t know how to do her job. She was not familiar with scheduled 1-1 meetings, but it is interesting how she perceived the word supervision to be negative and undermining.

While this article is about 1-1 line manager-direct report meetings, some of the key concepts are relevant to other types of 1-1 meetings and also group meetings. Many of the principles discussed here are widely relevant, as in all professions, the support and development opportunities provided are critical.

One of the first things I noticed early in my career was how much difference the various meetings we had contributed to our effectiveness. The types of meetings we had were individual line management supervision, team meetings, clinical and organizational consultation meetings, and training groups, among others. The frequency of most of these meetings was usually weekly. Not only did the combination of different meeting processes enable the quality of engagement required for the work, but it was also vital to help sustain the work. Before becoming a team manager, I noticed that effective management supervision had a significant impact on staff retention and ‘sickness’ absence rates. So, it has always been my view for over 35 years now that providing high-quality line management supervision is critical to high-quality performance.

One’s experience over time is a good measure. It is additionally helpful when this is added to by significant research in the field. I am indebted to many great practitioner-researchers over the years, some of whom are listed in the bibliography and references. I am also indebted to all the people I have had 1-1 meetings with throughout my career, especially those who I have met hundreds of times. I must have participated in over 10,000 1-1 meetings including, line management 1-1s (supervision), mentoring, coaching, consultancy, and clinical supervision.

The spark to write this article came from two recent books from different but complementary perspectives. The first is Dr. Anton Obholzer’s (2021) book – Workplace Intelligence. Obholzer is a psychiatrist, psychoanalyst, organizational consultant, and previous Chief Executive of the Tavistock & Portman NHS Trust, in the UK. He became interested in applying his professional knowledge to workplaces. The second is Dr. Steven G. Rogelberg’s book, Glad We Met: The Art and Science of 1:1 Meetings. Rogelberg is a vastly experienced and published professor of organizational science, management, and psychology from the USA (see appendix for a brief bio).

The spark to write this article came from two recent books from different but complementary perspectives. The first is Dr. Anton Obholzer’s (2021) book – Workplace Intelligence. Obholzer is a psychiatrist, psychoanalyst, organizational consultant, and previous Chief Executive of the Tavistock & Portman NHS Trust, in the UK. He became interested in applying his professional knowledge to workplaces. The second is Dr. Steven G. Rogelberg’s book, Glad We Met: The Art and Science of 1:1 Meetings. Rogelberg is a vastly experienced and published professor of organizational science, management, and psychology from the USA (see appendix for a brief bio).

They both talk from experience and Rogelberg has also carried out extensive quantitative research across many professions. This is hugely valuable as it has provided much-needed data. These books have affirmed my experience and view that there is a strong correlation between the quality of 1-1 manager-direct report meetings and performance. Improving the quality of 1-1 meetings is one of the most significant ways of improving overall performance and outcomes.

WHAT IS A 1-1 MEETING?

This definition by Rogelberg (2024, p.4) is a helpful starting point,

In the simplest sense, 1:1s refer to a regular and recurring time held between a manager and their directs to discuss topics such as the direct’s well-being, motivation, productivity, roadblocks, priorities, clarity of roles/assignments, alignment with other work activities, goals, coordination with others/the team, employee development, and career planning.

We can see that the range of issues involved is complex. In any profession, working with people carrying out challenging tasks can be complex on professional and personal levels. Therefore, carrying out effective 1-1 meetings crystalize the difficulties involved. People skills as well as technical knowledge are important. All work between people has a relational element and requires a degree of emotional intelligence. For example, attunement to feelings, empathy, and compassion. There must also be cultural sensitivity to help avoid misunderstandings. Also to be attuned to the way that power dynamics and discrimination can enter the meeting process and relationship.

In some fields of work such as therapeutic services for traumatized children the primary task of the work is essentially relational. This means that a high level of relational skills is especially important. As trauma is central to the work understanding the nature of trauma, how it might be manifested, and how to respond is vital. Weekly 1-1 meetings whether with a line manager, consultant, or mentor, will significantly improve the likelihood that signs of vicarious trauma and burnout are picked up early. 1-1 meetings in this context must be trauma-informed and effective in the way these issues are responded to. When this is done well the process contributes to emotional containment whereby the work can be thought about and made sense of (see, Ralph and Iszatt-White, 2016 – Who Contains the Container?). On this specialized and complex aspect of 1-1 meetings (usually referred to as supervision), these books also give a helpful understanding of what is involved,

• Janet Mattinson (1970) The Reflection Process in Casework Supervision

• Lynette Hughes and Paul Pengelly (1997) Staff Supervision in a Turbulent Environment: Managing Process and Task in Front-line Services

• Peter Hawkins and Robin Shohet (2006) Supervision in the Helping Professions

Often in the field I work in and others, the word support gets referred to as being a key factor. However, it is important to keep in mind that the word support also means helping a person to develop and be more effective in their work. It does not only mean being a good listening ear, though this is an essential part of it. The organizational consultant, Isabel Menzies Lyth (1979, p.222) explains the meaning of the manager’s role concerning staff support and the primary task,  “Rice (1963) has said that the effective performance of a primary task is a major source of satisfaction and that insofar as behaviour is adult and reality-based people are loath to surrender such satisfaction.

“Rice (1963) has said that the effective performance of a primary task is a major source of satisfaction and that insofar as behaviour is adult and reality-based people are loath to surrender such satisfaction.

The responsibility of management for effective task-performance is a contribution to staff support, both through positive job satisfaction and through protecting staff from the anxiety, guilt and depression that arise from inadequate task-performance.”

Therefore, it is supportive to focus on what is needed to do a job well. The word support has become a bit at odds with the concept of accountability. I tend to agree with the point made by Brené Brown (2018) that, “Clear is kind. Unclear is unkind.” - she gives a clear example,

Not getting clear with a colleague about your expectations because it feels too hard, yet holding them accountable or blaming them for not delivering is unkind.

Accountability and being clear should be encouraged in all directions. However, the manner of holding accountable is important (see Bregman, 2016). Avoiding it is not helpful to anyone and usually leads to a lack of development or deterioration. Rogelberg (p. 110) argues,

Accountability and kindness are not mutually exclusive in any way. Sometimes, holding people accountable is an act of kindness in of itself. Overall, being kind is essential to addressing personal needs and building a robust relationship. It also allows your messages of accountability and/or critical feedback to be more readily heard, as you intend them as kindness can break down walls of defensiveness and close-mindedness. It is also noteworthy that kindness begets kindness.

Referring to decades of research Gallup (2024, p.19) agrees about the importance of accountability,

Managers drive engagement through goal setting, regular, meaningful feedback and accountability. Gallup’s decades of research into effective management finds that a great manager builds an ongoing relationship with an employee grounded in respect, positivity, and an understanding of the employee’s unique gifts. Great managers help employees find meaning and reward in their work. As a result, employees take an interest in what they do, leading to higher productivity and enjoyment.

The manager must add value to their direct reports. This does not mean that the manager has all the answers, but it should mean that they know the type of questions to ask, and how to find solutions together when needed. There are many reasons why this is a challenging task. So, the first things that must be established are safety and trust. As Rogelberg explains (p.38), “One of the biggest values of the 1:1 is the ability to be frank with each other”. To achieve this a safe, protected, and reliable space is required. The scheduled 1-1 meeting in a suitable and confidential space is the ideal way of achieving a safe and productive working relationship. Rogelberg (p.11) states,

1:1s are the perfect opportunity to help others, give to others, and through both, experience the great intrinsic rewards of making a difference in the lives of others. When you have effective 1:1s, all lives are elevated—including your own.

He makes the point that this is true of virtually all occupations. It is a human need to develop, improve, make a difference, and feel that one’s contribution matters. It is hard to think of any job where this would not be desirable. In his book on Personal and Professional Development, Olson (2013, p.101) explains how our interest in development may be connected to the way we perceive the potential benefits,

“From what I’ve observed, within the general population, only about 10 percent of people (10 percent at most) are genuinely open to working on personal development. When you bring the dimension of happiness into it, when you show them what has been happening in the last fifteen years in happiness research, then suddenly that 10 percent becomes more like 50 percent.”

“From what I’ve observed, within the general population, only about 10 percent of people (10 percent at most) are genuinely open to working on personal development. When you bring the dimension of happiness into it, when you show them what has been happening in the last fifteen years in happiness research, then suddenly that 10 percent becomes more like 50 percent.”

Olson argues that if the focus on development is changed to one on happiness, then people’s interest is much greater. He says that development and happiness are interconnected. The research on what it takes to raise happiness correlates closely to what it takes to improve personal development. The lure of happiness is more powerful than the idea of development to motivate us to take on hard and even painful work.

DIFFERENT TYPES OF 1-1 MEETINGS

As well as the typical 1-1 meeting between a line manager and their direct report there may also be other types of meeting in place. Jacques and Clement (1991, p.300) make the responsibility of the line manager clear,

Immediate managers should deal with in-role issues. They must coach regularly with a view to helping subordinates to realize their full capabilities for the full opportunities which are available in the role.

Whatever the type of meeting, the chair/manager always has a key role and responsibility. The vital role is to keep the meeting on task according to the parameters that have been set. As well as the conscious explicit purpose of the meeting there are less transparent and unconscious dynamics involved (see Tomlinson, 2024). The work will be taken off task if these dynamics are not managed well. Obholzer (p.53) states,

If the meeting is well managed as regards task, boundaries, and time, chances are that there will only be minimal interference in its work by the presence of unconscious processes. The more the meeting runs in a laissez-faire or sloppy mode, the more are unconscious processes likely to make their appearance and interfere with the required work.

In addition to the line manager-direct report 1-1 meeting, other types of meetings can complement and be a helpful addition to the quality of support and development opportunities provided. As said, many of the principles in this article are relevant to all types of 1-1 meetings, and some are also relevant to group meetings. The type and number of regular meetings a professional is involved in will be related to the task and context. There is no one-size-fits-all approach. These are some of the possibilities.

Mentoring

A mentoring meeting process can be very helpful to focus on development. It is provided by someone who is experienced and can offer the mentee help, encouragement, and guidance in their professional challenges and development. The mentor may be a professional outside of the organization or if the organization is large enough, a senior manager ‘once removed’ from the mentee. The mentor once removed but inside the organization, was highly recommended by Jacques and Clement in their book Executive Leadership. The benefit of this model is that the mentor is not so caught up in the day-to-day management so can keep the focus more on ongoing development rather than problem-solving.

Consultation

A consultant, especially an external one who is not an employee is also able to offer a once-removed perspective. Not being caught up in the ‘thick of it’ and having a high level of experience can be very helpful (see Wilson, 2003, Obholzer, 2021). While a mentor is usually helpful in the general process of development a consultant can be used to zone in on a specific aspect of the work. A consultant usually brings a high level of expertise in a specific niche. Therefore, this can be a good complement to the more generic line management role.

Peer Supervision

This is where a group of peers meet to share their work and offer each other a listening ear, different perspectives, and potential solutions. This process may be chaired by one of the peers, or by a more senior manager, or a facilitator. This process can help establish collaboration with different perspectives, a shared connection, and supportiveness, and reduce the potential sense of isolation.

Other types of meetings that might take place, include coaching, clinical supervision, and reflective practice. In some situations, there may be the opportunity for a combination of meetings. For example, line management supervision, mentoring, and consultation. In these cases, the frequency of the line manager-direct report 1-1 meeting may not need to be so frequent. For example, instead of being weekly, it could be every 2-3 weeks.

THE VALUE OF A SCHEDULED MEETING IN A SAFE PROTECTED SPACE

Sometimes when line managers are asked why they do not have more frequent scheduled meetings the answer given is that ‘we check in with each other regularly’. Often phrases like my door is always open, and we chat regularly, etc. are used as if a scheduled meeting with a pre-planned agenda is the same as a check-in. The two things are connected but quite distinct.

Ad hoc conversations in the daily course of work can complement 1-1s but not substitute for them. Being approachable and finding time for team members is different from a focused, prepared-for, scheduled meeting. The thinking processes for each are different. For instance, catching someone unprepared and raising a challenging issue might be unfair and unhelpful. A safe working relationship is established by openness and putting the necessary conditions in place to ensure the reliable safety of a protected time and space. The space must be protected from distractions.

Passing conversations, catch-ups, and updates by nature are not usually deep. Neither is it possible to deal with complex and emotional issues where the consequences are potentially high. It is also human nature to avoid pain and deny difficulties. A more casual way of working feeds into these defensive avoidances. Sometimes we are not aware of something troubling until we sit down in a safe space with an attentive other. If we do not at least regularly pay attention to what is going on in our work and life there is a serious risk that unacknowledged issues either get acted out towards others or cause internal pain, physically and mentally. A lack of opportunity to acknowledge, think about, and try to understand difficulties in challenging work is a major cause of staff sickness, absence, and turnover, among other significant organizational symptoms. Obholzer (2021, p.134) explains this well when he talks about “in-house staff support systems”,

“These take a variety of forms. The worst form, in my view, is captured by the phrase, ‘my door is always open’. This is meant to show that the person concerned is always available for, and open to, contact with members of the organization. It may be so, but this, in itself, raises the question of what sort of management and/or leadership can be achieved when the individual is constantly available for interruption… While sounding open and friendly, it can actually have the opposite effect. One could interpret this dynamic as: ‘I cannot bother to set aside a regular time to meet with you, but if you can find your way through the obstacle course we might meet’. This process of contact is not conducive to good communication.”

“These take a variety of forms. The worst form, in my view, is captured by the phrase, ‘my door is always open’. This is meant to show that the person concerned is always available for, and open to, contact with members of the organization. It may be so, but this, in itself, raises the question of what sort of management and/or leadership can be achieved when the individual is constantly available for interruption… While sounding open and friendly, it can actually have the opposite effect. One could interpret this dynamic as: ‘I cannot bother to set aside a regular time to meet with you, but if you can find your way through the obstacle course we might meet’. This process of contact is not conducive to good communication.”

Open and Closed Doors

Interestingly, Obholzer picks out the ‘my door is always open’ as being the worst form of espoused staff support. Maybe the use of the term just means being friendly, responsive, and approachable. But it is misleading. A door always being open communicates the wrong message. It suggests that the person is always available and even invites regular disruption. It also suggests a lack of appropriate boundaries, which may undermine the development of oneself and others. Constant availability is not good for mature development. Development is often helped by having to work something out on one’s own and managing to wait.

In one organization I worked with the open-door concept was taken to the extreme. You could be in a meeting with one person with the door closed and someone else would open the door without knocking, walk in, and sit down. Unsurprisingly, the organization was in a chaotic state. Closed doors are sometimes necessary and healthy. The exception is when it becomes a defence to distance, avoid, and disconnect. We can make our appropriate availability clear without needing to suggest the door is always open.

However, good quality communication is vital in complex, emotional work where the consequences are high. Good is more than being friendly and chatting regularly. It is about creating a context where a deep level of communication can take place. It is the deep and sometimes unconscious matters that are the most troubling and if not worked with, often become the cause of trouble. Obholzer (p.135) explains why the scheduled protected space is so important to provide good quality attention,

Having a specific time set aside on a regular basis to meet with staff in relation to their work roles is essential. If this is respected by both sides, it opens successful channels of communication. But here, too, there are pitfalls. Constant interruption, taking telephone calls, looking at the computer screen rather than the individual concerned, reading and sending texts, all give a clear message: ‘I cannot really be bothered to give you my full attention’. Behaving in this manner encourages others to do the same: ‘If the boss can behave in this way, then it must also be acceptable for me’. This creates a climate of pseudo-attention and pseudo-communication that is likely to ‘infect’ the entire organization. What is not a good model for family and couple communication is certainly not a good model in institutional practice.

He goes on to explain the problem of emails, which are often used unhelpfully because important matters are not being attended to properly. It is common in organizations that do not do enough talking in depth that emails proliferate with emotional and unhelpful content. This is also, often a defence to avoid the more difficult work and to look like one is doing the work, especially when numerous people are unnecessarily copied into the email chain. Unsurprisingly, in this kind of culture things tend to get worse rather than better.

MEETING CONTENT

Once it is agreed that the scheduled 1-1 meeting is important then the value of it will be felt if the content is well organized. Content could be considered as what is on the agenda. Rogelberg (p.59) states,

The most important criterion governing matters to be talked about is that they be issues that preoccupy and nag the subordinate. (Andy Grove, Former CEO and Co-Founder, Intel)

And (p.60)

… the data suggest that agendas are helpful, but do not need to be detailed or highly structured for 1:1s to be effective.

While having a clear and well-planned agenda is important, content also includes the quality of the attention and experience. Making a commitment to the meeting and arriving well prepared, and on time gives the right kind of message. The way the meeting is conducted must reflect organizational values that are respectful, etc. As part of the meeting process, there should be a personal element. Rogelberg (p. 92) states,

Tacy Byham’s (2015) work does such a great job of highlighting the two types of needs to be fulfilled in a successful 1:1 process. Namely, an excellent 1:1 process addresses directs’ practical and personal needs.

And (p.112)

Satisfying Personal Needs Is Critical. While 1:1s are meant to address directs’ practical needs, they must also be conducted in a way that meets directs’ personal needs. Doing so ensures that directs feel included, respected, valued, heard, understood, and supported.

To get the balance right we need to take an interest in the person and not only the professional. It is important to get to know each other as people, with lives and interests outside of work. This helps to build a productive relationship. As Rogelberg (p.60) argues,

A key piece of a 1:1 is truly to get to know your direct, what is their personal story, and of great relevance, what drives them. This allows you to truly connect with your people. This connection is so important.

At the beginning of the meeting process, it is necessary to establish the expectations and purpose of the meeting. It will be helpful to keep in mind the values that are relevant to the meeting. Some ground rules can be agreed upon. For example, how will we carry out our discussions? On the one hand, this will evolve naturally. It can also be helpful to make explicit some of the approaches to learning and development. For example, it is ok to critique and challenge ways of thinking and doing things. There should be a two-way process where both are open to learning. A record of the meetings will be helpful to capture the agenda and key themes discussed, and any agreed actions, dated and signed. This helps with any follow-up on what has been discussed and agreed upon, and it improves a sense of accountability, both ways.

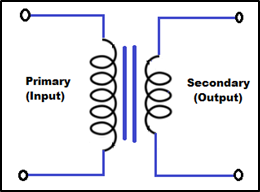

The quality of attention, psychological presence, and engagement are especially important. In general, presence is a key element of effective leadership (Kahn (1990, 1992), Friedman 1999). Friedman has referred to this as a non-anxious, self-differentiated presence, where the person can be connected and involved but also separate. This offers a containing and thoughtful space for difficult and powerful issues to be made sense of. To explain this process Friedman has used the metaphor of a transformer in an electrical circuit. The issue (anxiety) might enter the space (meeting) at 1000 volts and through the transformative process leave at 100 volts. Or it could be the other way around. Friedman (1999, p.232) states,

“To the extent that leaders and consultants can maintain a non-anxious presence in a highly energized anxiety field, they can have the same effects on that field that transformers have in an electrical circuit.”

“To the extent that leaders and consultants can maintain a non-anxious presence in a highly energized anxiety field, they can have the same effects on that field that transformers have in an electrical circuit.”

The manager in the meeting is responsible for the role of a transformer. However, where the senior person’s presence is not in good shape it can easily go the other way. This is why self-management and self-awareness are so important to effective management and leadership.

An important aspect to be observant of and discuss is the relational dynamic between the manager and direct report. As there are matters of authority involved it is always possible that powerful primitive feelings can arise in the relationship. This is especially so when the work is by nature, complex, emotional and relational, and high-risk. If the relational matters are reflected upon effectively useful insights can be gained. If they are not, the relationship may be at risk of becoming ineffective with negative consequences being acted out.

ENGAGEMENT AND PRESENCE

The international research across all industries by Gallup (2024) shows that employee engagement is the key influence on individual and organizational performance. Gallup provides analytics and management consulting to organizations globally. Their global reports feature, “annual findings from the world’s largest ongoing study of the employee experience. We examine how employees feel about their work and their lives, an important predictor of organizational resilience and performance”.

Not surprisingly, their research has found that the key issue affecting performance is employee engagement. And employee engagement is strongly associated with manager engagement. Gallup (2024, p.2) has found that 70% of all variances in team employee engagement correlate with the level of manager engagement. That is of major significance both for the quality of management in general and for the 1-1 meeting process. The need to engage and develop managers cannot be underestimated.

If the manager is not engaged the meeting process is not likely to help the direct report and may even have a negative impact. Gallup has studied the engagement levels of 2.5 million manager-led teams around the world and found that on average, only 15% of employees who work for a manager who does not meet with them regularly are engaged; managers who regularly meet with their employees almost tripled that level of engagement (in Rogelberg, p. 8). Khan (1990) was the first to write about the importance of engagement in his study, Psychological Conditions of Personal Engagement and Disengagement at Work. Zinger (2017) refers to Khan as the founding father of engagement. Khan states (1990, p.700),

“Personal engagement is the simultaneous employment and expression of a person’s “preferred self” in task behaviors that promote connections to work and to others, personal presence (physical, cognitive, and emotional), and active, full role performances. My premise is that people have dimensions of themselves that, given appropriate conditions, they prefer to use and express in the course of role performances.”

“Personal engagement is the simultaneous employment and expression of a person’s “preferred self” in task behaviors that promote connections to work and to others, personal presence (physical, cognitive, and emotional), and active, full role performances. My premise is that people have dimensions of themselves that, given appropriate conditions, they prefer to use and express in the course of role performances.”

On the opposite end, he explains disengagement,

“I defined personal disengagement as the uncoupling of selves from work roles; in disengagement, people withdraw and defend themselves physically, cognitively, or emotionally during role performances. The personal engagement and disengagement concepts developed here integrate the idea that people need both self-expression and self-employment in their work lives as a matter of course (Alderfer, 1972; Maslow, 1954).”

Kahn (1992) expanded upon the importance of psychological presence as a key part of engagement in, To Be Fully There: Psychological Presence at Work. Referring to Kahn’s work, Cardona (2003) claimed with the title of her paper,

The Manager's Most Precious Skill: The Capacity to be `Psychologically Present

In all fields of work and especially in trauma services the attuned attention of a manager is a great benefit to optimizing the performance and development of their direct reports. It can also have indirect knock-on benefits to others. It helps create a non-anxious, self-regulating, and capacity to think. In these conditions, the worker will be more likely to reflect ‘on action’ and ‘in action’ (Schön, 1983). It is likely to have a great impact on improving responsiveness and reducing reactiveness. People are more likely to feel safe enough to,

Employ the self without the fear of negative consequences (Khan, 1992, p. 333).

These concepts have gained momentum in recent years and have led to others such as Psychological Safety and Team Psychological Safety (Delizonna, 2017, Edmondson, 2019, Kim et al., 2020). While the nature of a manager’s presence is likely to be important in all professions, the precise nature of it will vary according to context. This is one of the reasons why context is so vital to leadership. As explained by the transformer metaphor, the kind of presence required in one context may not be helpful in another. Another useful way of thinking is to consider the manager as a model for what is expected of the direct report in the delivery of their work. Miller (1993) explains this well and makes these two key points,

1. The quality of the holding environment of staff is the main determinant of the quality of the holding environment that they can provide for clients.

2. The quality of the holding environment of staff is mainly created by the form of organization and by the process of management.

Everything that goes on in the meeting also provides a model for what is likely to go on outside of it. For example, if a direct report feels listened to, valued, and treated with respect they are more likely to mirror those qualities with others. There are few opportunities better than a 1-1 meeting to model appropriate boundaries, clarity of purpose, reliability, attentiveness, and the balance between seriousness and lightness, among many other important qualities.

FOCUS ON DEVELOPMENT

For a 1-1 meeting process to be effective there needs to be a focus on development. Inevitably, there will be a need for problem-solving and going over significant events, but these discussions can also include a focus on what have we learned. How has an experience given insight that can be used in the future? What further work can we do to understand the issue better? In the modern-day workplace, we must not underestimate the importance of professional and personal development. This is at the top of Maslow’s (1943) hierarchy of needs – self-actualization. Rogelberg (p.11) highlights how this is important across most types of work and how the 1-1 process can be rewarding to both who are involved,

1:1s are the perfect opportunity to help others, give to others, and through both, experience the great intrinsic rewards of making a difference in the lives of others. When you have effective 1:1s, all lives are elevated—including your own. The general assumption is that 1:1s are not for those who, say, work with their hands and use their physical abilities to complete their work (e.g., blue-collar, pink-collar, and working-class type jobs) such as construction workers, mechanics, custodial workers, truck drivers, nurses, and machine operators. I don’t fully understand why anyone would feel this way. The desire to thrive, overcome obstacles, develop meaningful relationships, and feel seen/heard is not unique to any particular job type or profession.Development is so important to human nature that if we do not work on it effectively, there is a likelihood of disengagement. To help keep a focus on development all information that can be shared outside of the meeting must be done efficiently through emails, data systems, and other updates. It is not helpful to use the meeting to track metrics but more to be informed in advance of where things are at. Discussion should focus on growth, development, and solutions. As this can be challenging work, we cannot always expect the discussion to flow easily. Rogelberg (p. 119) points out the need to,

Get comfortable with silence as a manager. It can be tempting to want to fill the silence if and when it happens, but keep in mind that silence is often an indication of contemplation rather than awkwardness or a lack of engagement. You can even encourage moments of silence by telling your directs to pause whenever they need to so they can think through their ideas. This does not have to be a rushed process.

Thinking and pausing, rather than reacting is vital in all types of roles and professions. In trauma-informed services, it is vital. In trauma work, the tendency towards reactivity is so high, unhelpful, and potentially retraumatizing. The same can be said of any work that involves crisis and high levels of stress.

PEOPLE MANAGEMENT AND LEADERSHIP

Managers and leaders have many demands upon their time and attention. Each leader will have their way of prioritizing, sometimes led by the present circumstances, their preferences, and abilities. Often a leader does not prioritize the development of their team and direct reports. For example, in response to the question, ‘Why don’t you have more frequent 1-1 meetings’ the answer might be, ‘I don’t have enough time’. Rogelberg (p.4) argues against the misguided nature of this,

1:1s are a core leadership responsibility. The best leaders recognize that 1:1s are not an add-on to the job; 1:1s ARE the job of a leader.

While there may be exceptions to this I agree with his point. Effective 1-1 as well as team meetings can boost development and quality of performance. Rogelberg (p.7) claims that this is strongly supported by research and that “1:1s are arguably one of the most important activities you can do as a leader”. So, this should save time by reducing the number of problems arising due to errors, mistakes, and poor work. Additionally, major savings in cost and time, and performance improvements can be expected as engagement goes together with staff retention. Effective 1-1s continuously build on connection, trust, and safety which are crucial ingredients to engagement and positive work. Every 1-1 meeting is a potential investment in building these qualities and outcomes.

ISSUES TO CONSIDER REGARDING TIME AND FREQUENCY

These are helpful questions to ask when considering time and frequency,

1. How complex is the work task? (i.e. if it is working with young people who are in care having suffered complex trauma, the work is highly complex).

2. How much are emotional issues part of the work? Some work is highly emotional and some so little that you can be fairly switched off, though those kinds of jobs are less common than they were.

3. How serious are the potential consequences of not doing the job well or making a mistake? In some jobs, the consequences can be a matter of life and death, and in others small.

4. How experienced is the worker and competent from technical and self-management perspectives? Less experienced workers may need more frequent meetings.

5. How important are relationships in the work task? In some work, the relational context, safety, and trust can outweigh the technical abilities. In others, technical skill and experience are paramount. A higher frequency will be needed in a new manager-direct report relationship to help build the relationship.

If the 1-1 meeting is between a manager and direct report one of the key objectives and responsibilities is that the manager must assist the direct report in their development. This means that the manager must be able to help the direct report make sense of their work, learn from it, find solutions, and make progress. It is also helpful if the manager can help calm and steady the natural anxieties of someone less experienced. Of course, the direct report on occasion will also assist the manager and the manager will learn from the process. But if there is not a sufficient gap between the two the manager will struggle to add any value. It will be more like a peer relationship but confused by the nature of the authority between the two. In this case, the direct report is likely to become frustrated and the manager may feel threatened and become defensive.

Assuming that the manager can be useful to the direct report one of the first things to do is to agree upon the meeting frequency. The five questions above can be a helpful guideline. If the work is complex, emotional, and with potentially serious consequences a weekly meeting would not be excessive. That would mean that over a year the direct report would be getting around 40 hours 1-1 time from their manager. In an average year of 1800 hours at work – the worker would be receiving about 1 hour of 1-1 attention for every 40 hours of work in a task that is complex, emotional, and potentially high in risk.

If the work is not complex, not emotional, and is with low consequences the frequency could be less. For example, every 2-4 weeks. Bear in mind that people do not develop by magic and an experienced manager, coach, or mentor can make a huge difference. So, even if the task is simple, improvements in quality, efficiency, and commitment to the work can make a huge difference in the quality of performance. As a customer, we know how much difference it makes when a worker takes care and goes the extra mile, however low-paid their job might be. People usually take care and invest themselves in the work when they feel that their work and personal needs are also being taken care of and invested in.

Rogelberg’s (p. xix) research found that across all industries, the more frequent the 1-1s, up to weekly compared with fortnightly or monthly the better the outcomes in engagement and performance. In a study of 200 managers, the frequency was found to be: Weekly 49%. Bi-weekly 22%. Monthly 15%. Quarterly 2% (p.23). Rogelberg found that on average weekly 1-1s correlated with the highest level of performance. To conclude (p.24) he states,

Weekly 1:1s aligns most with employee preferences in general across job level and country.

O.C. Tanner is the global leader in software and services that improve workplace culture through meaningful employee experiences. Their research (2021, p.35-36) found remarkably similar results to Rogelberg in the correlation between meeting frequency and performance. In 2021, O.C. Tanner synthesized multiple research studies involving more than 40,000 employees and leaders from 20 countries. This research showed a statistically significant difference in the effectiveness of one-to-ones held weekly versus every other week (biweekly) and monthly. The results are captured below,

Weekly One–To–Ones – Outcomes - Compared To Biweekly

• Engagement: +58%

• Fearfulness: –47%

• Personal productivity: +31%

• Purpose: +19%

• Opportunity: +24%

• Success: +15%

• Appreciation: +24%

• Wellbeing: +23%

• Leadership: +36%

• Burnout: –15%

Every metric is improved. Engagement is up by 58%, and fearfulness is down by 47%. This research was carried out following the pandemic when working from home was the new norm. Greater employee isolation was one of the consequences. This has continued with many organizations adopting the hybrid way of working. Engagement and fearfulness are hugely relevant to performance quality and other important matters such as well-being and burnout. O.C. Tanner argues that the nature of work has changed, and organizational leadership and culture must adapt. Attention must be paid to this, especially in occupations that are challenging, stressful, and relatively isolating. Improving meeting frequency and quality is a key factor.

How long should the meeting be?

As well as the frequency of meetings the length of each meeting is also important. Does a meeting need 30 minutes, an hour, or longer? One consideration may be to do with the time needed for in-depth discussion and processing of complex issues. If meetings are more frequent, weekly for instance, one meeting could be for 1 hour and the other for 30 minutes. The tasks of the different meetings could be differentiated. One person I work with has found it helpful to alternate between a more strategic and a more reflective type of meeting. Or it could be a more problem-solving and a more development-focused meeting. In some therapeutic services for traumatized children, a high level of external regulation has tended to lead to a very structured meeting process. This can end up feeling like a tick box style of 1-1 meeting to evidence that key issues are being covered. If this type of meeting must take place there could be a less structured and more reflective type of meeting in-between.

Not all meetings need to be an hour, sometimes 30-45 minutes could be very helpful. Does an hour-long meeting just become a habit? The time allocated will tend to be used, whether it is needed or not. With frequency, there can be too much of a gap between meetings, so the thread and sense of continuity are lost, or too little of a gap, and not much gets done or changes in between. The balance is important and Obholzer (p.125) reminds us that,

… what happens between formal sessions is at least as important as what happens in the sessions themselves. This time provides the space to think about matters raised and to see whether ideas considered in the sessions are relevant to everyday life. Perhaps most importantly, do they offer a more constructive way for life and work?

Whatever the agreed frequency and length of time for a meeting, making it clear and holding the boundaries firmly is most likely to have positive benefits. Sometimes the meeting content may be anticipated as challenging and anxiety-provoking. The feelings involved can be difficult, stressful, and even distressing. Clarity of expectations, boundaries, and reliability should help reduce anxiety and improve a feeling of security from which people can engage. Meetings at the same time and frequency become a routine that allows people to worry about the less predictable aspects of their work. The reliability of a well-run meeting process can provide an anchor that also enables people to be more effective outside of the meeting. Especially in work that involves significant risk and uncertainty, it helps to make whatever is within control, dependable, and easier to follow.

Punctuality: Talking about why it is important to be on time, or even better a few minutes early, Duckworth (2016, p.267) says,

Punctuality: Talking about why it is important to be on time, or even better a few minutes early, Duckworth (2016, p.267) says,

“It’s about respect. It’s about details. It’s about excellence.”

Setting a clear expectation about punctuality is important. The more senior person needs to role model this so that the expectation is clear. By paying attention to this, any changes in patterns and attitudes can be more easily observed.

As the reliability of meetings is key to their success, avoid cancellations and time changes as far as possible. Regular unplanned changes undermine confidence, safety, and trust. It may also give the impression that the meeting is not valued and therefore undermine its purpose. Give attendees as much advance notice as possible if a cancellation or change is needed (Tomlinson, 2024). Regularly canceling 1-1s can give the message that the meeting and therefore the direct report is not a priority. Rogelberg (p.33-34) states,

1:1s should only be canceled if you truly have no other option. 1:1s are an investment in your people and your team, thus should be held sacred… If you must cancel because of some type of emergency, be sure to take the initiative and reschedule it right away.

Nowadays there is the question of whether 1-1 meetings are in-person or virtual. So far, the evidence from research is not clear one way or the other (Rogelberg, p.41). It makes sense to monitor this and see what your experience tells you about the effectiveness of each. There are probably many variables involved.

CHALLENGE AND AMBIVALENCE

As frequent 1-1 meetings are essential for growth, development, effectiveness, and achievement at all levels from individual to organization, we might wonder why valuing them is not more predominant and why the resistance can be so strong. These are some of the possible reasons.

1. Some professionals and managers may not be aware or may be skeptical of the rationale behind 1-1 meetings and the evidence that underpins it.

Some managers may not have experienced especially positive 1-1 meetings, and some will have experienced unhelpful or damaging processes. In these cases, the person may not have much confidence that 1-1 meetings can be helpful. As a result, Rogelberg (p. xiii) points out that people may even dread meetings, fearing that only something negative will happen. If Olson’s view that making progress on development makes people happy is correct, then the opposite is likely to be true. Not making progress on development makes people unhappy. If the 1-1 meeting is about development (happiness, as Olson points out), whether the meeting works well or not and makes a difference is fundamental to the likely interest, engagement, and commitment to the process.

If a manager does not have a positive model of 1-1 meetings there may also be little guidance available on how to carry out meetings effectively.

2. Some people may think there is no need for regular meetings as they are doing well enough.

The reality of doing well enough may be true to some extent but it could also be a defence against a more challenging reality. Eurich (2018) claims,

In our nearly five-year research program on the subject, we’ve discovered that although 95% of people think they’re self-aware, only 10 to 15% are.

A gap also tends to be found when professionals rate how well they are doing. Liker (2004, p.87) claimed in his study of Toyota’s lean production model, that most business processes are 90% waste and 10% valued added work. Dr. Michael Maccoby (2007, p.91), in his research on senior professionals and managers at high-tech companies, such as HP, IBM, Intel, and Texas Instruments, says that he was astonished to find that of all the highly educated professionals he looked at only 22% were highly effective. Rogelberg’s research (p. xvi) concurs,

… leaders’ self-ratings of their skills in conducting 1:1s appear to be inflated, suggesting that leaders think they are doing a better job at leading 1:1s than they actually are.

If the gap is as big as suggested any process that might look at narrowing the gap is bound to be met with some resistance by the supervisee and supervisor. It can be hard, even painful work to close the gap. Unfortunately, defensive responses or routines as Argyris (1985) says,

“… as well as protecting us against pain”, “… also prevent us from learning how to reduce what causes the pain in the first place”. (in, Senge, 1990, p.234)

3. Spending time thinking in meetings can feel like it is not a priority.

Most organizations have pressing priorities centred around getting work done and completing tasks. Spending time in meetings can feel counterproductive in busy work environments. However, according to Rogelberg’s research carrying out regular scheduled 1-1 meetings is one of the most cost-effective uses of time. Reflective practice should also always be a part of 1-1 meetings. Thiel et al., (2012) argue that the consequences of not taking time to reflect can result in sub-optimization of leadership actions and decisions; which may lead to poor judgment and even ethical lapses. They claim,

Thus, setting aside time and space to think could be considered a leadership imperative.

4. Learning is challenging and never-ending, though the rewards of being a life-long learner are great.

Effective 1-1 meetings must promote learning for both parties. At some level, we would like to think we know what we need to know. Learning gets us in touch with what we do not know, which can make us feel vulnerable. Chris Argyris (1991) claims that it can be people at the top of an organization who find it the hardest to learn. Often their successes have been based on technical skills. They think they are smart, and the process of reflection and learning can be challenging as it implies not knowing. Not knowing a solution. Argyris illustrates this point,

Put simply, because many professionals are almost always successful at what they do, they rarely experience failure. And because they have rarely failed, they have never learned how to learn from failure. So, whenever their single-loop learning strategies go wrong, they become defensive, screen out criticism, and put the “blame” on anyone and everyone but themselves. In short, their ability to learn shuts down precisely at the moment they need it the most.

5. Development is a challenge.

Before an infant can walk, they fall over many times. Or as an Olympic gold medal ice skater said, I succeeded because I fell on my bum a thousand times. With encouragement and support, this might not feel too bad, but we know that even with support the frustration and feelings of impotence are hard to bear. Fear of not knowing and being able to do something is not easy to overcome. One way we might manage this is by setting ourselves low goals. To stay in the comfort zone of what we know we can do.

Another possibility that Dweck (2016) has pointed out and that can get a grip at the highest levels of an organization – is to hide failure and exaggerate success. Dweck and others have shown that in the wrong kind of environment how children and adults will lie to avoid exposure to failure. Dweck argues this is more likely where there is an emphasis on the idea that success is based on talent, rather than arduous work and practice. Olson (2013, p.101) explains how our interest in development may be connected to the way we perceive the potential benefits,

Far more people have a strong desire to be happy than a strong desire to develop themselves to a fuller potential. “Personal development” sounds to most people like work, and who wants to work harder than they are already working? But “happiness” doesn’t sound like work. It sounds like … well, it sounds like being happier.

6. Not knowing is usually more anxiety-provoking than knowing.

An important aspect of 1-1 meetings is to affirm what we know and have learned and to identify what we don’t know and are working on. Not knowing and uncertainty can be difficult, especially so when we are in a difficult and threatening situation. As Friedman (1999) implied in the title of his classic book, “A Failure of Nerve: Leadership in the Age of the Quick Fix”, leadership is not easy. Being able to tolerate not knowing does not mean we stay in that position, but we stay in it long enough to find a better understanding and response to a problem. Not being able to tolerate the anxiety involved is likely to lead to reactive, counterproductive actions.

7. The avoidance of pain is a human instinct individually and in groups.

Friedman (2007, p.67) states the reality for any person, family, or organization that wants to improve,

There is no way out of a chronic condition unless one is willing to go through an acute, temporarily more painful phase.

The problem is as Friedman (p.67) says, “that chronic conditions, precisely because they are more bearable, also tend to be more withering over time”. Most of us and organizations are likely to have a chronic condition or two! The familiar phrase ‘growing pains’ is a good metaphor for what is involved if we want to learn, grow, and mature as individuals, groups, and organizations. To grow we must let go of defences that are often dysfunctional. For example, thriving in a crisis, such as putting out the fire gives a sense of accomplishment. In organizations and teams that struggle to hold regular effective scheduled meetings, there are often regular unplanned crises.

8. Effective 1-1 discussions expose our thinking.

This means that errors in thinking might become obvious to ourselves and others. As well as being helpful, this can also evoke strong feelings such as embarrassment, humiliation, and fear of negative consequences. Senge (1990, p.231) links our defensiveness with our formative experiences,

For most of us, exposing our reasoning is threatening because we are afraid that people will find errors in it. The perceived threat from exposing our thinking starts early in life and, for most of us, is steadily reinforced in school—remember the trauma of being called on and not having the "right answer"—and later in work.

Edmondson (2019) in her book ‘The Fearless Organization’ has shown how fear is one of the main reasons people do not express their thoughts and ideas. Unless people can express themselves openly, even if meetings happen, they are not likely to be useful and productive. This highlights how vital it is to work on establishing and maintaining trust.

9. Useful and challenging 1-1 discussions might evoke fear of conflict.

A useful discussion may require debate, questioning, analysis, reflection, and critical thinking. Most of the time this can feel positive and a helpful way of learning. However, people might also be familiar with debates and arguments that become a matter of right and wrong, winners and losers. This can become a hostile climate where people can easily become upset with each other. If so, a reparative process will be needed to restore a safe working relationship. This is one of the reasons why more frequent meetings help to create a sense of safety where difficult and productive conversations are possible. Less frequent meetings are more likely to get stuck at a superficial level of become conflictual in an unhelpful way.

WHAT CAN WE DO TO WORK ON IMPROVING 1-1 MEETINGS?

It may be difficult to know where to start so it may be helpful to begin with some reflective questions and analysis of the present situation.

1) Is the purpose of 1-1 meetings clear and how often do you have them?

2) How well do the meetings work – from both sides – do they feel helpful, useful, and productive?

3) What is the level of engagement like for individuals and the organization as a whole?

4) Are there signs that people are developing well?

5) Do people have a development plan to which they are committed?

6) Are there signs of disengagement, poor performance, high turnover, and sickness rates?

The answers to these questions should help you to identify if any significant action is needed. The action could be that the meetings seem to work well but are not frequent enough. If you are effective at carrying out 1-1 meetings, increasing the frequency may be the best way to improve. If as Gladwell (2008) says, it takes 10,000 of deliberate practice to become a master at something – you will double your progress by increasing meetings from 4 -2 weeks, or 2 – 1. Increasing the frequency may also help meetings to work better because of the stronger connection, being better tuned in, improved safety, etc.

If meetings do not work well and there is no confidence in what to do a review of the whole process may be necessary. Hopefully, this article provides a helpful starting point along with the other articles and books referenced. Rogelberg’s book gives many guidelines and tools on how to carry out 1-1 meetings. But if you are aiming to make a significant change you may need to find some mentoring/training type of guidance.

CONCLUSION This article has discussed the value of 1-1 meetings between a manager and a direct report. As well as the evidence for this being based on experience, the research in recent years by professionals such as Rogelberg and those at Gallup has been hugely affirmative.

This article has discussed the value of 1-1 meetings between a manager and a direct report. As well as the evidence for this being based on experience, the research in recent years by professionals such as Rogelberg and those at Gallup has been hugely affirmative.

It is recognized that the nature of these meetings will vary according to circumstances and context. However, the key principles are largely relevant across all industries. A useful guide for working out how often you should have a 1-1 meeting is to consider,

• The complexity of the work involved

• The emotional and relational content of the work

• The risks involved and the consequences if the work is not carried out well

• How experienced is the worker

As a rule of thumb the higher the work scores in these factors the more time for connecting, processing, and thinking will be necessary. Therefore, people who are carrying out high-end tasks such as working with traumatized young people, will need the most regular meetings, such as weekly or bi-weekly. Ideally, there should be training available to help with the challenge of the task. If not, at least a mentoring process for the manager carrying out meetings with someone suitably experienced and skilled.

Gallup and other research have shown that employee engagement is critical to positive organizational performance and outcomes and manager engagement is the most influential factor in employee engagement. The 1-1 meeting between the manager and direct report is at the centre of engagement. The evidence referred to in this paper suggests that investing in the development of high-quality 1-1 meetings is likely to be highly cost-effective on many levels. Rogelberg (p. xiv) claims that when organizations make 1:1 meetings “the pillar of their leadership they can radically change their cultures and productivity as a whole”.

Appendix - Dr. Steven G. Rogelberg Brief Biography

Steven G. Rogelberg is a professor of Organizational Science, Management, and Psychology and the founding Director of Organizational Science at UNC, Charlotte. He has over 100 publications addressing issues such as team effectiveness, leadership, engagement, health and employee well-being, meetings at work, and organizational research methods. He is the editor of the Journal of Business and Psychology. Dr. Rogelberg has received over $2,500,000 of external grant funding including from the National Science Foundation.

For a full wiki biography click here. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Steven_Rogelberg

REFERENCES AND BIBLIOGRAPHY

Alderfer, C. P. (1972) Human Needs in Organizational Settings, New York: Free Press of Glencoe

Argyris, C. (1985) Strategy, Change, and Defensive Routines, Boston: Pitman

Argyris, C. (1991) Teaching Smart People How to Learn, in, Harvard Business Review, May-June 1991, https://hbr.org/1991/05/teaching-smart-people-how-to-learn

Bregman, P. (2016) The Right Way to Hold People Accountable, in, Harvard Business Review,

https://hbr.org/2016/01/the-right-way-to-hold-people-accountable

Brown, B. (2018) Clear is Kind. Unclear is Unkind.

https://brenebrown.com/articles/2018/10/15/clear-is-kind-unclear-is-unkind/

Byham, T. M. and Wellins, R. (2015) Your First Leadership Job: How Catalyst Leaders Bring out the Best in Others, John Wiley & Sons

Cardona, F. (2003) The Manager's Most Precious Skill: The Capacity to be `Psychologically Present', in, Organisational & Social Dynamics, 3(2)

Delizonna, L. (2017) High Performing Teams Need Psychological Safety. Here’s How to Create it, in, Harvard Business Review,

https://hbr.org/2017/08/high-performing-teams-need-psychological-safety-heres-how-to-create-it?utm_medium=social&utm_campaign=hbr&utm_source=LinkedIn&tpcc=orgsocial_edit

Dweck, C. S. (2016) Mindset: The New Psychology of Success, New York: Penguin Random House L.L.C.

Edmondson, A.C. (2019) The Fearless Organization: Creating Psychological Safety in the Workplace for Learning, Innovation, and Growth, Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons

Eurich, T. (2018) Difficult Conversations: Working with People who aren’t Self-aware, in, Harvard Business Review, https://hbr.org/2018/10/working-with-people-who-arent-self-aware

Friedman, E.H. (1999) A Failure of Nerve: Leadership in the Age of the Quick Fix, New York: Church Publishing, Inc.

Friedman, E.H. (2007) A Failure of Nerve: Leadership in the Age of the Quick Fix: 10th Anniversary Revised Edition, New York: Seabury Books

Gallup Report (2024) State of the Global Workplace: The Voice of the World’s Employees, Gallup Inc., https://www.gallup.com/workplace/349484/state-of-the-global-workplace.aspx

Gladwell, M. (2008) Outliers: The Story of Success, New York, Boston. London: Little, Brown and Company

Hawkins, P. and Shohet, R. (2006) Supervision in the Helping Professions, London: YHT Ltd

Hughes, L. and Pengelly, P. (1997) Staff Supervision in a Turbulent Environment: Managing Process and Task in Front-line Services, London: Jessica Kingsley

Jaques, E. and Clement, S.D. (1991) Executive Leadership: A Practical Guide to Managing Complexity, Basil Blackwell: Cason Hall and Co. Publishers

Kahn, W. A. (1992) `To be Fully There: Psychological Presence at Work', in, Human Relations, 45: 321-350.

Kahn, W.A. (1990) Psychological Conditions of Personal Engagement and Disengagement at Work, in, Academy of Management Journal, 1990, Vol. 33, No. 4, 692-724.

Kim, S., Lee, H. and Connerton, T.P. (2020) How Psychological Safety Affects Team Performance: Mediating Role of Efficacy and Learning Behavior, in, Frontiers in Psychology Journal, 24th July 2020, Seoul, South Korea, https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01581/full

Liker, J.K. (2004) The Toyota Way: 14 Management Principles from the World’s Greatest Manufacturer, New York, Chicago, San Francisco, Lisbon, London, Madrid, Mexico City, Milan, New Delhi, San Juan, Seoul, Singapore, Sydney, Toronto: McGraw-Hill

Maccoby, M. (2007) Narcissistic Leaders: Who Succeeds and Who Fails, Boston, Massachusetts: Harvard Business School Press

Maslow, A.H. (1954) Motivation and Personality, New York: Harper & Row

Maslow, A.H. (1943) A Theory of Human Motivation, in, The Journal of Psychological Review, Vol 50, No. 4, https://www.academia.edu/9415670/A_Theory_of_Human_Motivation_Abraham_H_Maslow_Psychological_Review_Vol_50_No_4_July_1943

Mattinson, J. (1970) The Reflection Process in Casework Supervision, Tavistock Institute of Marital Studies

Menzies Lyth, I. (1979) Staff Support Systems: Task And Anti-Task in Adolescent Institutions (Originally a Paper Read to the Conference of The Association for the Psychiatric Study of Adolescents, July 1974), in, Menzies Lyth, I. (1988) Containing Anxiety in Institutions: Selected Essays Vol. 1, London: Free Association Books, https://www.johnwhitwell.co.uk/child-care-general-archive/task-and-anti-task-in-adolescent-institutions

Miller, E.J. (1993) The Healthy Organisation - Creating a Holding Environment: Conditions for Psychological Security, The Tavistock Institute

https://www.johnwhitwell.co.uk/child-care-general-archive/the-healthy-organization-by-eric-miller/

Obholzer, A. (2021) Workplace Intelligence: Unconscious Forces and How to Manage Them, London and New York: Routledge

O.C. Tanner (2021) Global Culture Report: Crisis

https://www.octanner.com/global-culture-report/2021-crisis

Olson, J. (2013) The Slight Edge: Turning Simple Disciplines into Massive Success and Happiness, Plano, Texas: Success

Ralph, N.D. and Iszatt-White, M. (2016) Who Contains the Container? Creating a Holding Environment for Practicing Leaders, @, Conference: British Academy of Management, September 2016: Thriving in Turbulent Times

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/307477422_Who_contains_the_container_Creating_a_holding_environment_for_practicing_leaders

Rice, A.K. (1963) The Enterprise and its Environment, London: Tavistock Publications

Risk and Resilience UK - Vicarious Trauma: A Toolkit for Organisations and Individuals

www.risk-and-resilience.co.uk

Rogelberg, S. G. (2024) Glad We Met: The Art and Science of 1:1 Meetings, New York: Oxford University Press

Schön, D. (1983) The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action, London: Temple

Senge, P.M. (1990) The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization, Currency, Random House

Thiel, C. E., Bagdasarov, Z., Harkrider, L., Johnson, J. F., and Mumford, M. D. (2012) Leader Ethical Decision-Making in Organizations: Strategies for Sensemaking, in, Journal of Business Ethics, 107(1), 49-64, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/254426750_Leader_Ethical_Decision-Making_in_Organizations_Strategies_for_Sensemaking

Tomlinson, P. (2024) Effective Workplace Meetings: Task, Leadership, Dynamics, and Culture

https://www.patricktomlinson.com/effective-workplace-meetings-task-leadership-dynamics-and-culture-patrick-tomlinson-2024/98

Van der Kolk, B. A. (2005) Developmental Trauma Disorder: Toward a Rational Diagnosis for Children with Complex Trauma Histories, in, Psychiatric Annals, 35(5), 401-408

Wilson, P. (2003) Consultation and Supervision, Chapter 14, p.220-232, in, Adrian Ward, Kajetan Kasinski, Jane Pooley and Alan Worthington (Eds) (2003) Therapeutic Communities for Children and Young People, London and Philadelphia: Jessica Kingsley

Zinger, D. (2017) William Kahn: Q&A With the Founding Father of Engagement (Part 1), in, bobmorris.biz: Blogging on Business,

https://bobmorris.biz/william-kahn-qa-with-the-founding-father-of-engagement-part-1

Files

Please leave a comment

Next Steps - If you have a question please use the button below. If you would like to find out more

or discuss a particular requirement with Patrick, please book a free exploratory meeting

Ask a question or

Book a free meeting